On The Silver Globe

Lunar Trilogy

“We escaped from Earth, but Death, that powerful queen of earth tribes traveled through space with us.” — Jerzy Żuławski, The Lunar Trilogy

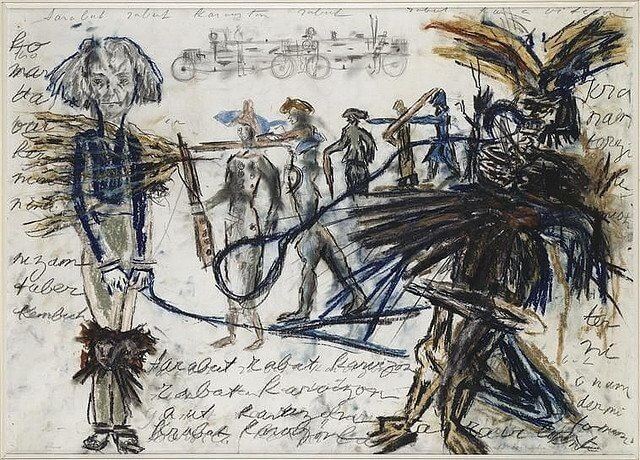

Deserts often function as a speculative topos, a space of formlessness and alterity from which to think outside the familiar. They mark the space of life’s absence, the risk of a return to the nonliving, or the uncharted horizon of new possibilities for life. Deviating from our well-worn maps of intelligibility, deserts offer a philosophical topology where unmediated forces exchange in anomalous ways.1 For early Science Fiction authors writing from the relatively affluent cities of Western Europe, like Jules Verne and H.G. Wells, the moon was a romantic terra incognita for imaginative extrapolation and utopian world-building, if not colonialist expansion and extraction. For Jerzy Żuławski of occupied Poland, then torn between three competing empires and oppressed under foreign rule, the deserts of the moon were a hostile landscape of collapse and extinction with little hope for survival, echoing the hellish struggles of not only his homeland but the human spirit.

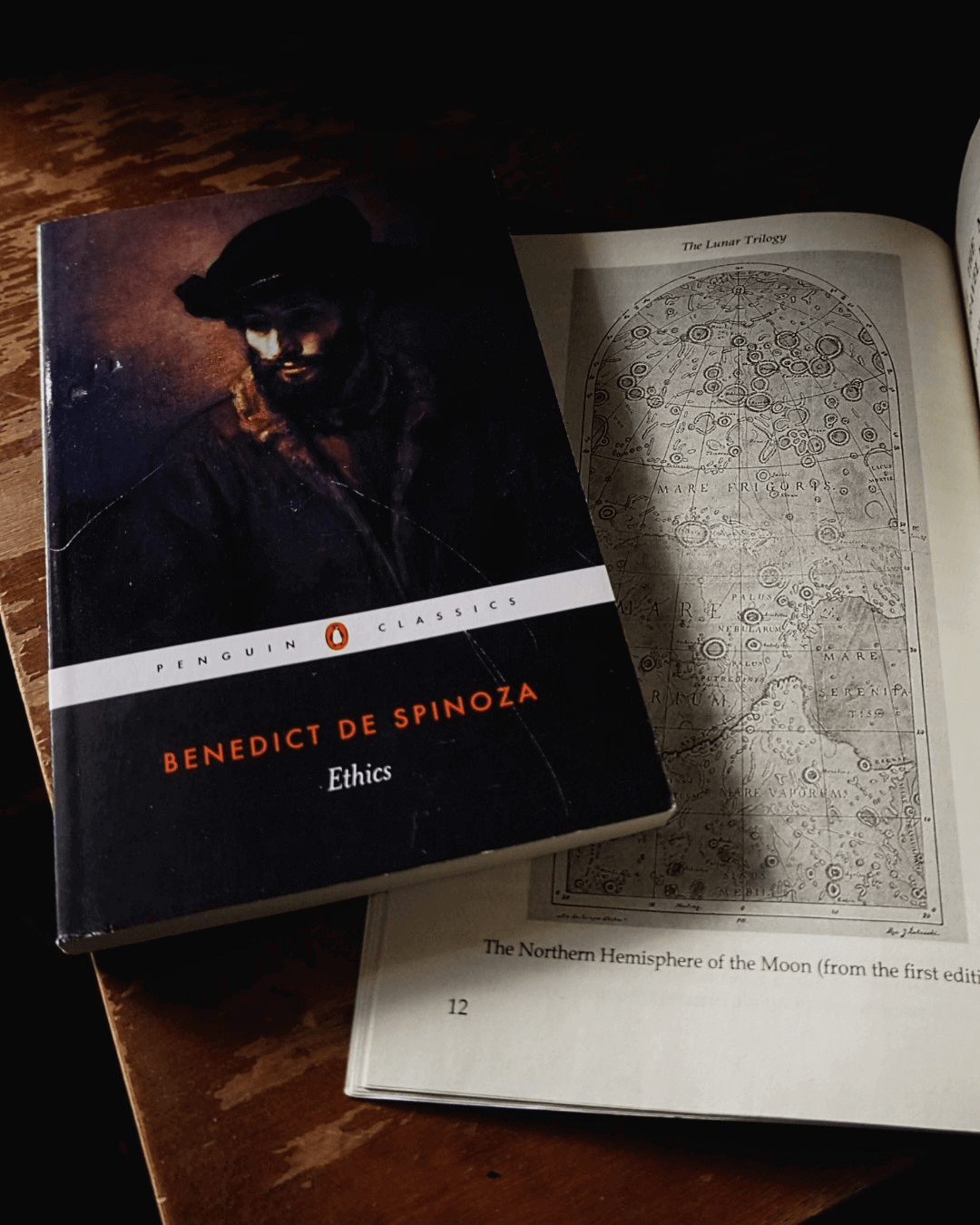

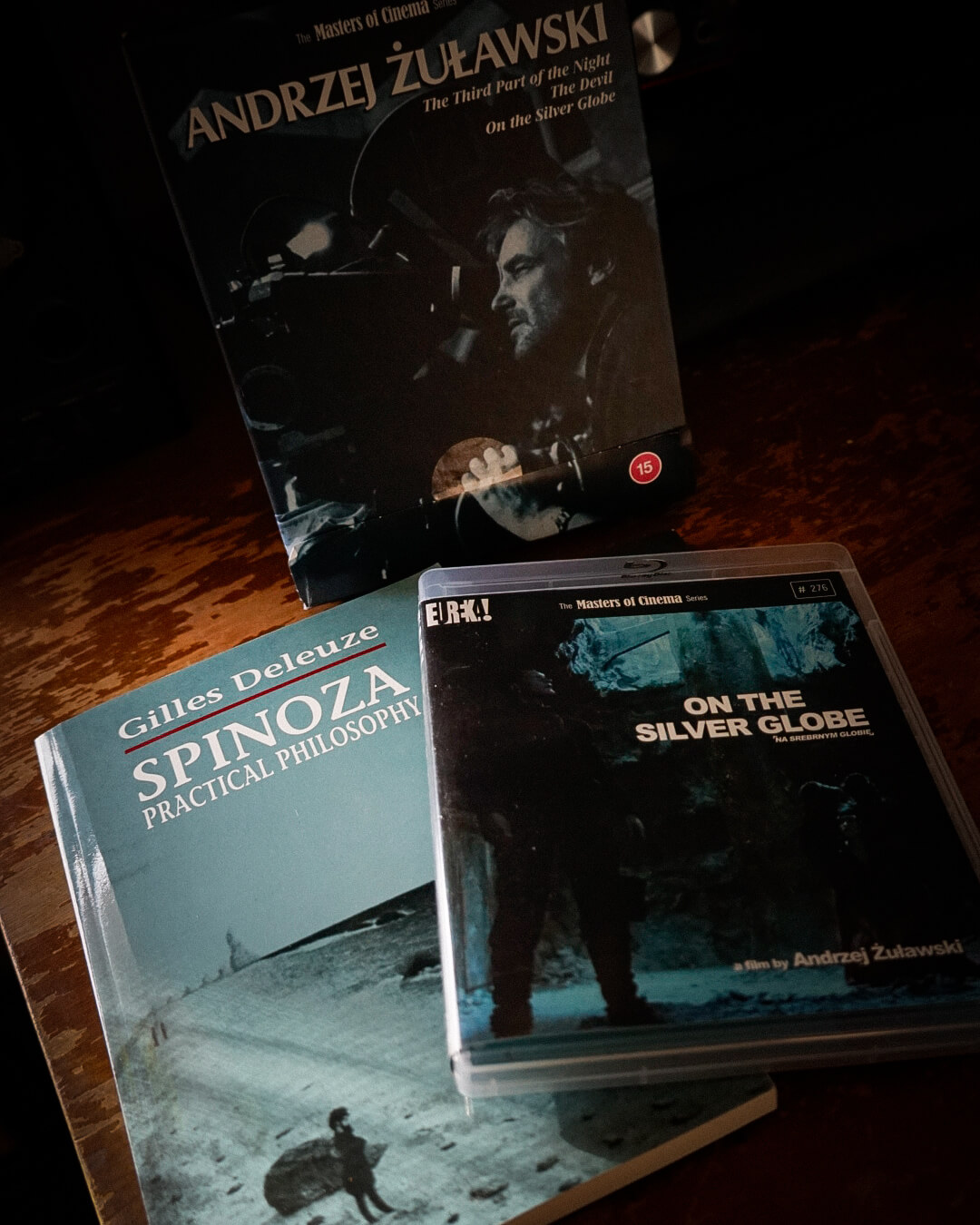

An avid alpinist, Żuławski spent much of his time in the rocky peaks of Poland’s Tatra mountains - a sublime, desert-like landscape that renders the human being insignificant. He studied philosophy under positivist Richard Avenarius, translated works of Schopenhauer and Nietzsche into Polish, and wrote his dissertation on The Problem of Causality in Spinoza (1899). His philosophical worldview was a flavour of synthetic monism, inspired by Spinoza’s Deus sive Natura, where the spiritual and material are complementary aspects of one divine substance.2 Writing in the romantic adventure and symbolist period of Young Poland, he employed SF as a method to model his theory of history, the processes by which “reality becomes overgrown with myth.”3 The role of the artist was to express the Absolute through the baring of one’s naga dusza (naked soul).4 Navigating the philosophical uncertainties of modernity — what Nietzsche characterized as a metaphysical desert or wasteland in the aftermath of the death of God — Żuławski posed the same questions Spinoza once had: Why are people so deeply irrational? Why do they fight for their bondage as if it was their freedom? Why does a religion that invokes love and joy inspire violence and intolerance?

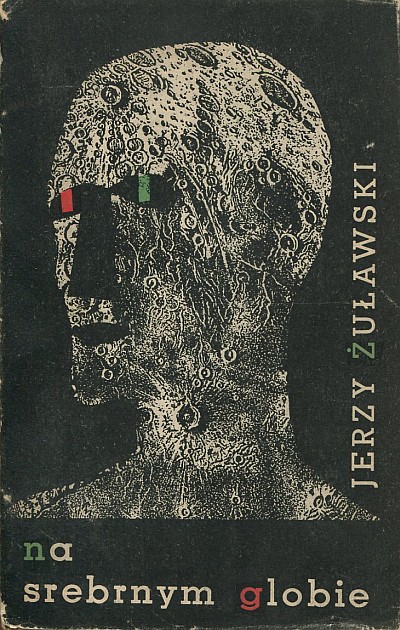

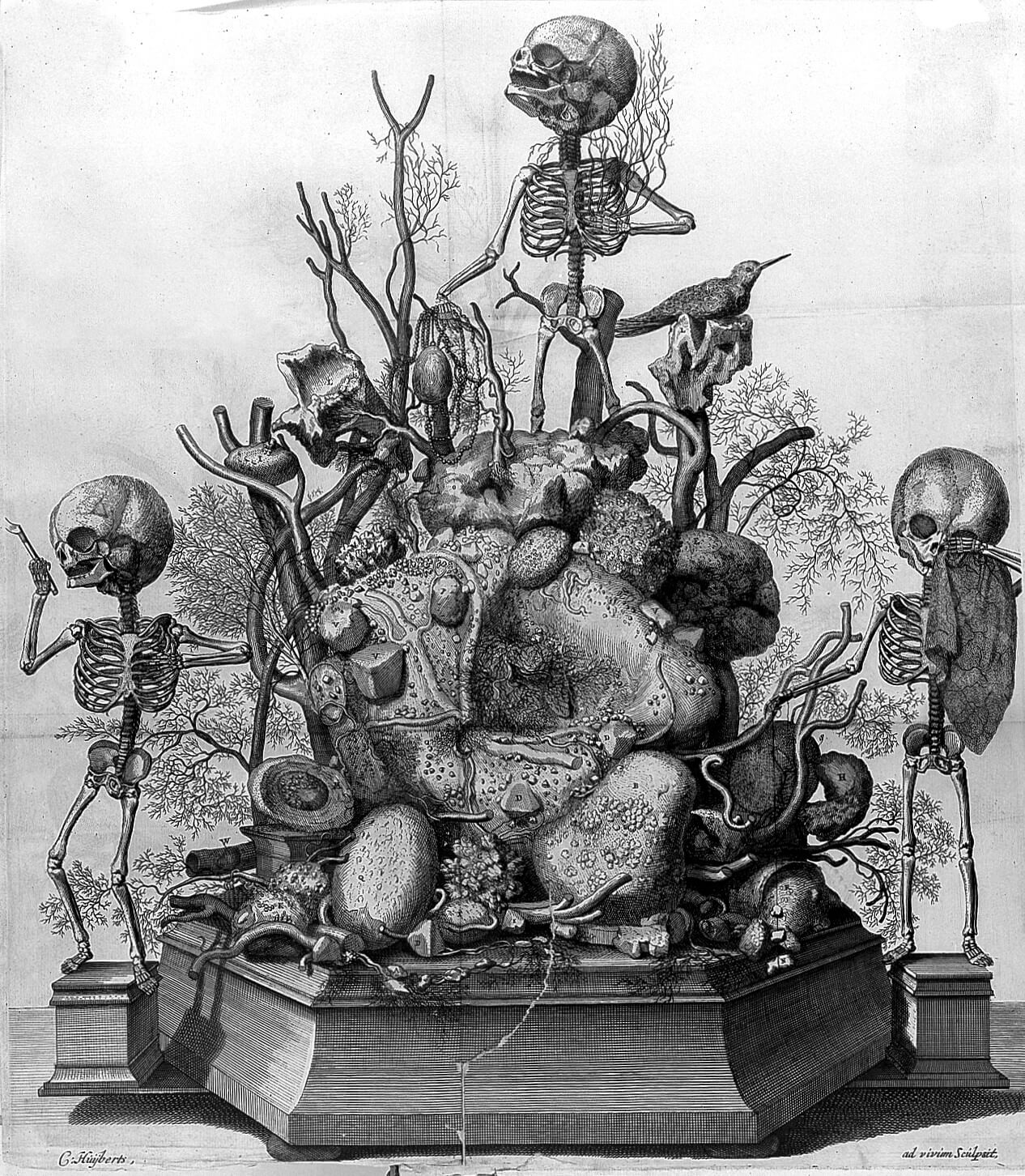

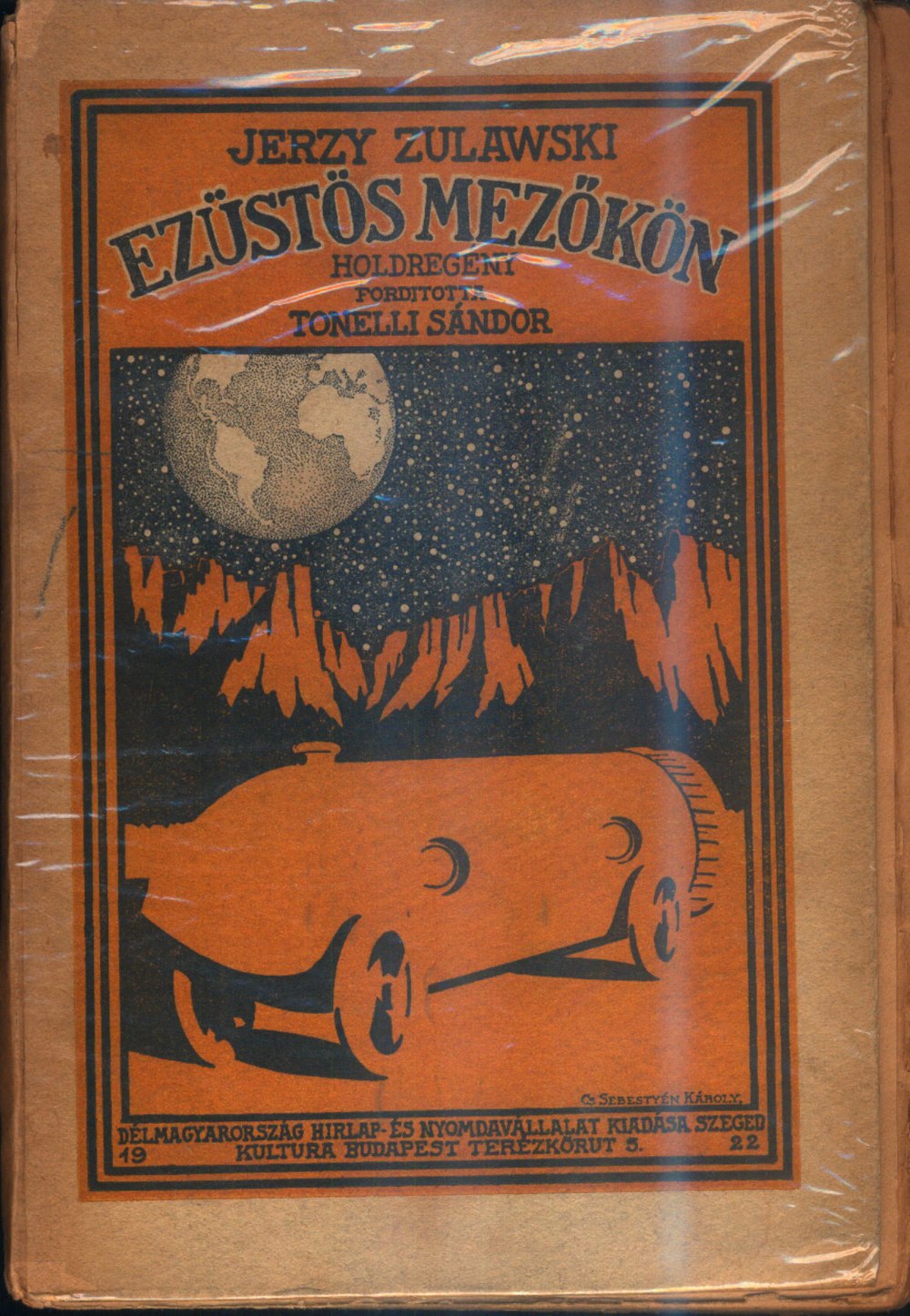

Polish Cover of ‘On The Silver Globe’

Polish Cover of ‘On The Silver Globe’

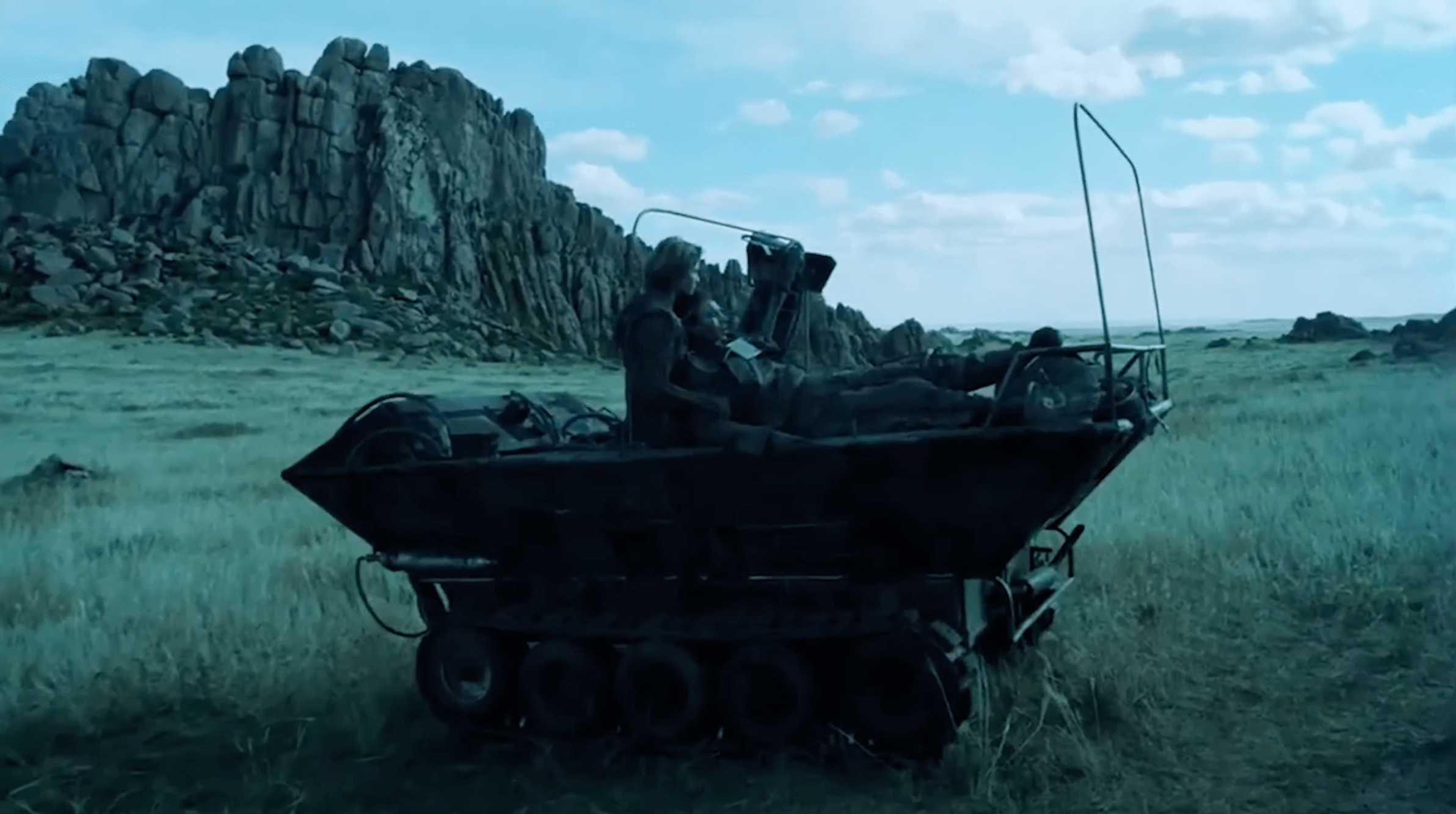

The first book in Żuławski’s The Lunar Trilogy (1901-1911) is the diary left by a member of an expedition of dissident space pioneers traveling across a lunar desert in search of a habitable oasis on the dark side of the moon. Confined in a lunar rover, the “lunatics” descend into an “immense world of void and stone, whiteness and blackness” haunted by “seas of darkness” and the “enigmatic chill and icy gloom of abysmal rocky fissures.”3 After many trials and tribulations, they finally reach their destination and establish a small colony of Selenites, a new lunar civilization doomed to repeat the mistakes of those on earth.

As we (children of colonialist empire) should well know, deserts, as terra nullius (territory without a master), are never truly uninhabited. War ensues between the lunar colony and the ancient, indigenous civilization of szernowie, or Sherns. The Sherns are bird-like demons with electrifying (and impregnating) tentacles who communicate telepathically through colored lights radiating from their phosphorescent foreheads. Over several generations, the lunar colony’s collective knowledge fragments. They invent a religion around the coming of a messiah, a human astronaut, who will free them from enslavement to the Sherns and return them to the planet of their ancestors, Earth. When that astronaut finally arrives, he is initially accepted as messiah but unable to fulfill the prophecy is made an outcast and brutally crucified.

Żuławski’s trilogy explores themes of human suffering, spiritual impoverishment, and messianic hope. It challenges religious dogma, the corruption of institutionalized power, and the limits of technological progress and scientific rationality. It is a bleak criticism of totalitarianism, the naivety of egalitarian utopianism and anti-intellectual authoritarianism that consolidates power by suppressing knowledge and proliferating misinformation. The religion invented by the lunar colony functions as an imperative set of laws demanding obedience and faith while obscuring the harsh reality and real cause of their suffering. The trilogy concludes back on Earth amidst a wilderness of conflicting narratives around historical events, including the invention of a weapon that threatens a catastrophic end to humanity (anticipating, a generation beforehand, the invention of the atomic bomb).2 Lacking adequate understanding of themselves and the world, driven by fear, illusion and superstition, humanity ultimately succumbs to what Spinoza called the sad passions.

Sad Passions

“We are driven about in many ways by external causes, and … like waves on the sea, driven by contrary winds, we toss about, not knowing our outcome and fate.” —Spinoza, Ethics

Jerzy Żuławski expanded his dissertation on Spinoza into what became a popular book of philosophy in Poland, Benedict Spinoza, Man and Achievement (1902).4 In Spinoza’s unified theory, all of creation is an expression of one substance, God or Nature. This substance has infinite attributes, of which thought and extension are known to us, expressed as finite modes. All modes are dynamic compositions of internal relations immanent to substance and have no external, static essence in themselves. Our ideas, emotions, desires and sensations are affects that are never independent from vectors of causality that intersect all existence.5 Completely separating mind from extension is meaningless abstraction. An early precursor to modern materialism, Spinoza’s radical contribution to Western philosophy was in emphasizing the primacy of the material world and the body as foundational in the constitution of our shared reality. 6

Spinoza called conatus the innate striving of each mode to preserve its existence by enhancing its capacity to act, its potential to affect and be affected in the world. As human beings, we value relations relative to how they enhance or diminish our conatus. Joyous affects are those that increase our capacity to act and sad passions are those that decrease it. In Spinoza’s deterministic universe, freedom is not about an absence of causality but understanding one’s relative place within it.5 Passive reactions to sad passions is akin to slavery. Through meditating on causal relations, the common happiness of all, and the interconnectedness of all things, we reduce our passive reactions to causal forces and increase our capacity to act independently. In having adequate knowledge that connects affects to their real causes, we master our sad passions, become the sufficient cause of our actions, and consequently relatively self-determined and free. Through refining our intellect and knowledge of eternity —an impersonal and indifferent nature to our own— we increase our joy and freedom.5

“Man acts out of egoism, but this egoism expressed by the drive for self-preservation, leading him to pursue his own happiness and good, also necessarily leads him to virtue and love of God, which are the highest happiness. Man gains the strength… through knowledge, which is both freedom and gives him immortality. Everything bad is the result of… the incompleteness of his knowledge, it is slavery and misfortune. Virtue… is happiness itself; A man does not overcome his passions in order to achieve happiness, but he overcomes them only insofar as he is happy, that is, powerful and free.” —Jerzy Żuławski

In championing rationalist self-determination over emotional bondage and passive obedience to external authority, Spinoza denounced three types of people: the slave, bound by sad passions; the tyrant, who exploits sad passions for power; and the priest, saddened by the human condition in general, forming a moralist trinity united in their hatred of life.6

“In despotic statecraft, the supreme and essential mystery is to hoodwink the subjects, and to mask the fear, which keeps them down, with the specious garb of religion, so that men may fight as bravely for slavery as for safety, and count it not shame but highest honor to risk their blood and lives for the vainglory of a tyrant.” —Spinoza, Ethics

Cosmic Pessimism

“If we picture to ourselves roughly as far as we can the sum total of misery, pain, and suffering of every kind on which the sun shines in its course, we shall admit that it would have been much better if it had been just as impossible for the sun to produce the phenomenon of life on earth, as on the moon, and the surface of the earth, like that of the moon, had still been in a crystalline state. We can also regard our life as a uselessly disturbing episode in the blissful repose of nothingness.” —Schopenhauer, Parerga & Paralipomena

Another significant influence for Jerzy Żuławski was Arthur Schopenhauer. A century after Spinoza, Schopenhauer had a starkly different view of the universe, not as a rational and orderly system, but as a fiery wheel, turned endlessly by a blind and irrational striving which he called the will.

Central to Schopenhauer’s philosophy is his development of Kant’s distinction between noumena — unknowable reality in-itself — and phenomena — the world as it appears to us as representation. Similar to Kant, the principle of individuation — the process by which perception and cognition differentiates the world into distinct objects and events, including our subjectivity, through space, time, and causality — is grounded in the mind independent of experience. However, unlike Kant, Schopenhauer argued one does have direct, albeit limited, empirical and intuitive knowledge of existence in-itself through one’s inner experience. Our desires or passions — often irrational and obscure to us, anticipating Nietzsche’s drives and Freud’s unconscious — are manifestations of the one will.

“My body and my will are one.”7 The body is the phenomenal form of the will, which itself is the noumenal form of the body. All things similarly strive for existence, perceived as instances of a universal, undifferentiated will which “knows neither time, nor beginning nor end, nor the bounds of a given individuality.”7 One is lived through by the will, but unlike Spinoza’s self-preserving conatus, the will is aimless, chaotic and the origin of all suffering. Reason aids us in understanding the world but it is ultimately subordinate to and fulfills the demands of the will. While Spinoza’s conatus affirms life and its rational order, Schopenhauer’s will undermines it, portraying life as the “unceasing motion” of desire and despair tumbling toward death, wherein “all of whom exist for a while only by devouring one another.”8

Existence is suffering the insatiable striving of the will, as the satisfaction of one’s desire gives way to another in a constant cycle of yearning and dissatisfaction, depriving us of true freedom and self-determination. There is no redemption, except possibly a fleeting repose from suffering through aesthetic contemplation and ascetic negation of egoistic desires “by assuming a decisive stand in opposition to nature”, a “sacrifice of one’s own self” through “the complete self-abolition and negation of the will.”7 In this state of willlessness, when one is free from the illusions of one’s ego and sees behind the artificial divisions of individuation, the will is experienced as indifferent and unknowable nothingness. At his best, Schopenhauer advocates compassion and ethical living to mitigate suffering, recognizing the pain of others as one’s own. He does not offer us joy or autonomy, but rather a sober recognition our existence, and perhaps, amidst all the wickedness, a momentary tranquility he refers to as “ocean-like calmness of the spirit.”7

“What remains after the complete abolition of the will is, for all who are still full of the will, assuredly nothing. But also conversely, to those in whom the will has turned and denied itself, this very real well-versed in Christian Gnostic traditions, is - nothing.” —Schopenhauer, The World as Will and Representation

Żuławski was also well-versed in Christian Gnostic traditions that emphasized personal spiritual enlightenment over orthodox dogma and institutional authority. Schopenhauer, while inspired primarily by the Upanishads and Buddhism, also recognized it was the Gnostics “who taught precisely pessimism and asceticism.”7 Gnosticism posited a dualistic cosmogony, distinguishing between a superior, hidden God and a lesser, malevolent demiurge responsible for a flawed material world and the existence of evil. Salvation was found through direct knowledge of this hidden divinity, sometimes symbolized with feminine imagery, via mystical or esoteric insight. Gnosis was not primarily rational knowledge but rather insight into the true nature of the world. (Pagels) The Gnostics understood their organizing principle was mythos rather than logos. Texts were to be interpreted allegorically, not literally, without any dogmatic interpretation enforced by authority. Schopenhauer took Gnostic teachings as the more truthful expression of the Gospels, in contrast to the optimistic narratives of orthodox Christianity, and identified the will with the gnostic demiurge.9 The material world, marked by suffering and injustice, was not the creation of a benevolent deity but a cosmic mistake.

In The Lunar Trilogy, the last remaining astronaut from the lunar expedition withdraws inwardly, estranged from the feral and incestuous selenite children born on the moon. After distress over his unrequited passion for the children’s mother, the only woman in the expedition, he spends his life obsessing over returning home to Earth. The selenite children age much faster than those on Earth, and as time passes, the astronaut’s teachings and intentions are misunderstood and distorted by the colony, leading to the emergence of a fanatic cult around this seemingly supernatural “Old Man” who never dies. In yielding to his pessimism, and choosing ascetic resignation to his fate rather than taking action and leading the colony, the tragic figure surrenders to personal despair. As Schopenhauer said of himself, “the old man, stricken in years, totters about or rests in a corner, now only a shadow, a ghost, of his former self… the moment of dying may be similar to that of waking from a heavy nightmare.”7 The old man’s final act of hope is returning to the lunar landing site and firing his video diary by cannon back to Earth before taking his last breath of depleted air.

“Suppose the human race were removed to a Utopia where everything grew automatically and pigeons flew about ready roasted… then people would die of boredom or hang themselves, or else they would fight, throttle, and murder one another and so cause themselves more suffering than is now laid upon them by nature.” —Schopenhauer, Parerga & Paralipomena

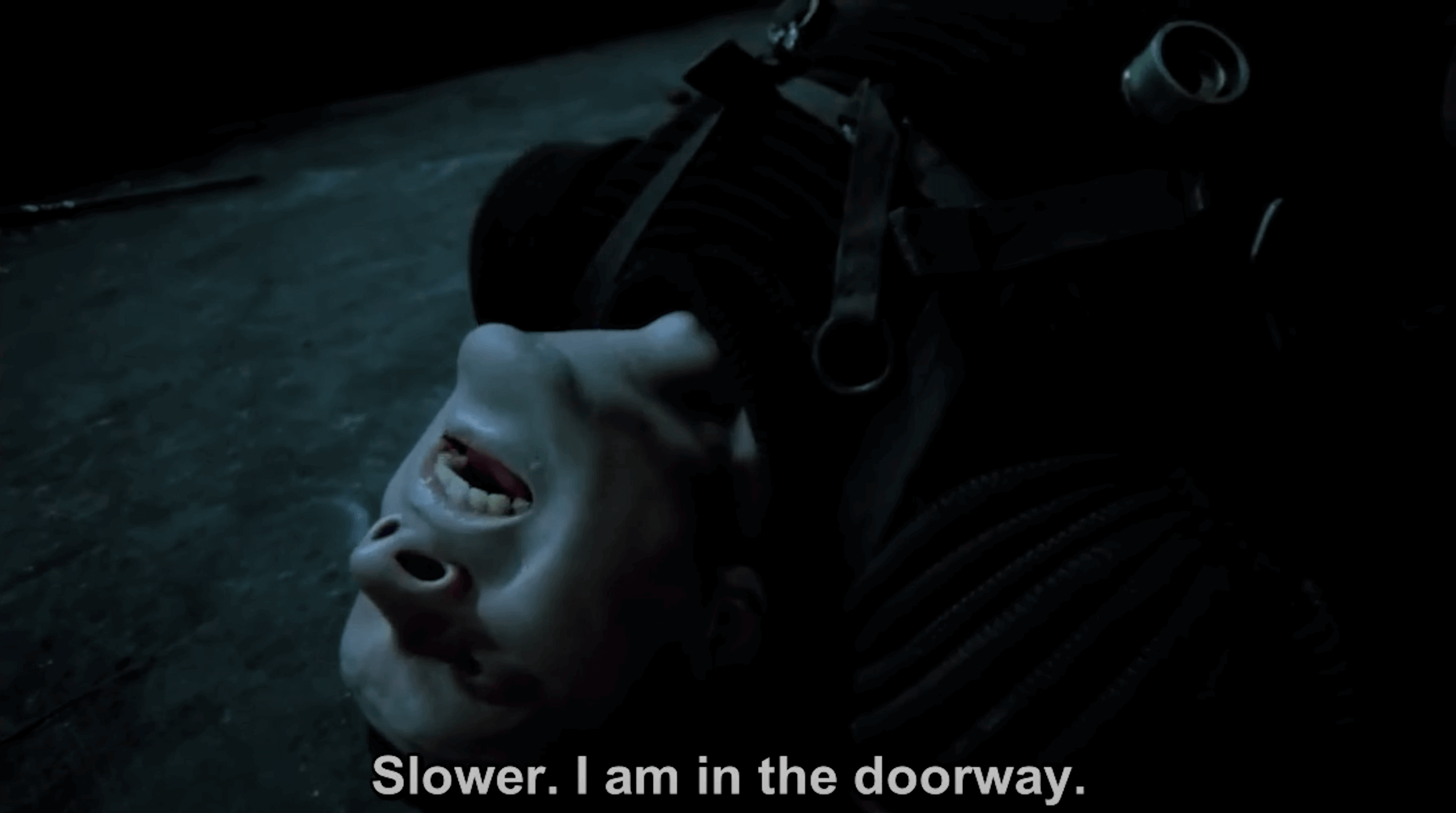

On The Silver Globe

“Why are you elsewhere, where nothing exists?” —Tomasz II, On The Silver Globe

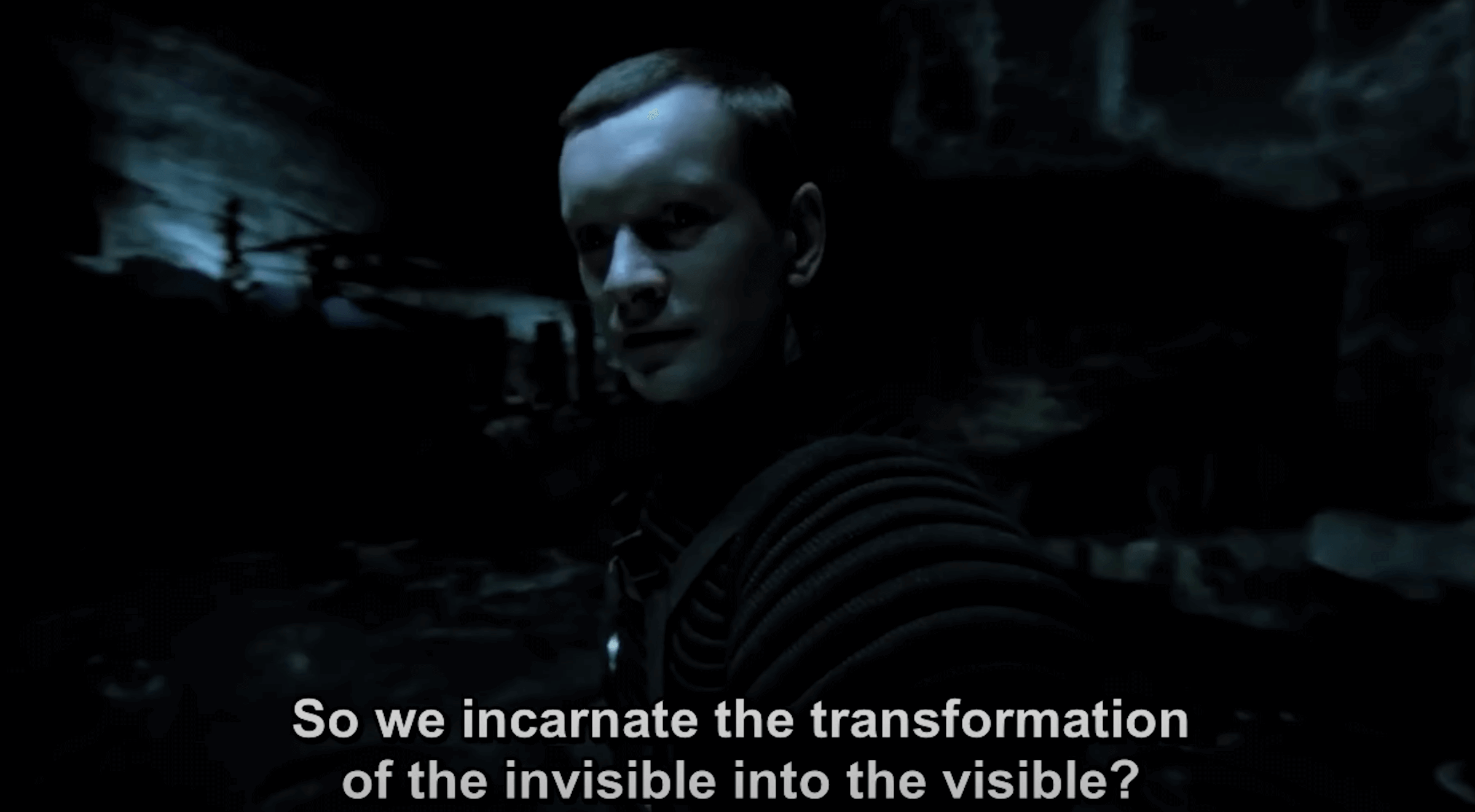

Fast-forward to 1976 — two generations after the death of Jerzy Żuławski — Poland is a communist state under the influence of growing economic and political turmoil of the Soviet Union. Andrzej Żuławski, the great nephew of Jerzy Żuławski and an already controversial filmmaker by this time, undertakes the film adaptation of his great uncle’s The Lunar Trilogy, titled after its first book On The Silver Globe.

Rather than the moon, Żuławski’s film takes place on a planet that resembles Earth. Filmed with a meager (or beleaguered) budget along the Polish coastline, the Gobi deserts of Mongolia, and medieval salt mines a thousand feet underneath Wieliczka, Poland, production hardships must have rivaled almost that of a perilous journey across the moon. As Polish film scholar Daniel Bird observes, it was monetary and technical constraints, as much as artistic preference, that influenced Żuławski’s embrace of artifice over realism.10 Surreal sets, ritual costumes, over-the-top theatrical acting, a montage of cryptic dialogue (which Żuławski reportedly often improvised on the fly from fragments of gnostic and mystical texts), and manifestly choreographed battle scenes that are more like dance than combat — all remind the audience that they are witnessing a constructed narrative suggesting symbolic and timeless cosmic cycles, rather than a representation of everyday reality.

At the heart of Żuławski’s cinema is the spectacle,10 famously articulated a generation before Żuławski by outsider artist Antonin Artaud. Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty was an experience that violently assaults the senses with the aim to uncover primal, subconscious forces that subvert traditional narrative structures and bypass intellectual engagement in favor of direct, visceral impact.11 Żuławski claimed he and Artaud drank from the same stream, as did the Polish avant-garde before them — such as theatre director Jerzy Grotowski, and the eccentric Witkacy (a colleague of Jerzy Żuławski’s), who painted portraits under the influence of narcotics from caffeine to peyote (the more exotic the narcotic the higher the sale price).10 Artaud himself claimed to have participated in peyote rites in Mexico in 1936. The final act of Żuławski’s film begins with the protagonist, Jacek, seemingly astral traveling to the Silver Globe by ingesting a hallucinogen procured from a shaman. As the film approaches its end, it becomes increasingly obscure whether the story is taking place on Earth, on another planet, or somewhere in the depths of the human psyche.

“In our present state of degeneration it is through the skin that metaphysics must be made to re-enter our minds.” —Artaud, The Theatre and its Double

Following this experimental current, the film is a metaphysical odyssey into the interior deserts of the soul, a psychedelic ethnology framed through the existential crisis of a speculative future humanity. While deviating significantly in certain aspects from his great uncle’s SF classic, Żuławski’s film stays relatively close to the original narrative. The film is divided into three parts, analogous with the Old and New Testaments, and roughly aligned with the first two books of the trilogy, namely On The Silver Globe, about the original lunar expedition; The Conqueror, about the arrival of the astronaut and alleged messiah; and ending with the beginning of the third book, The Old Earth.

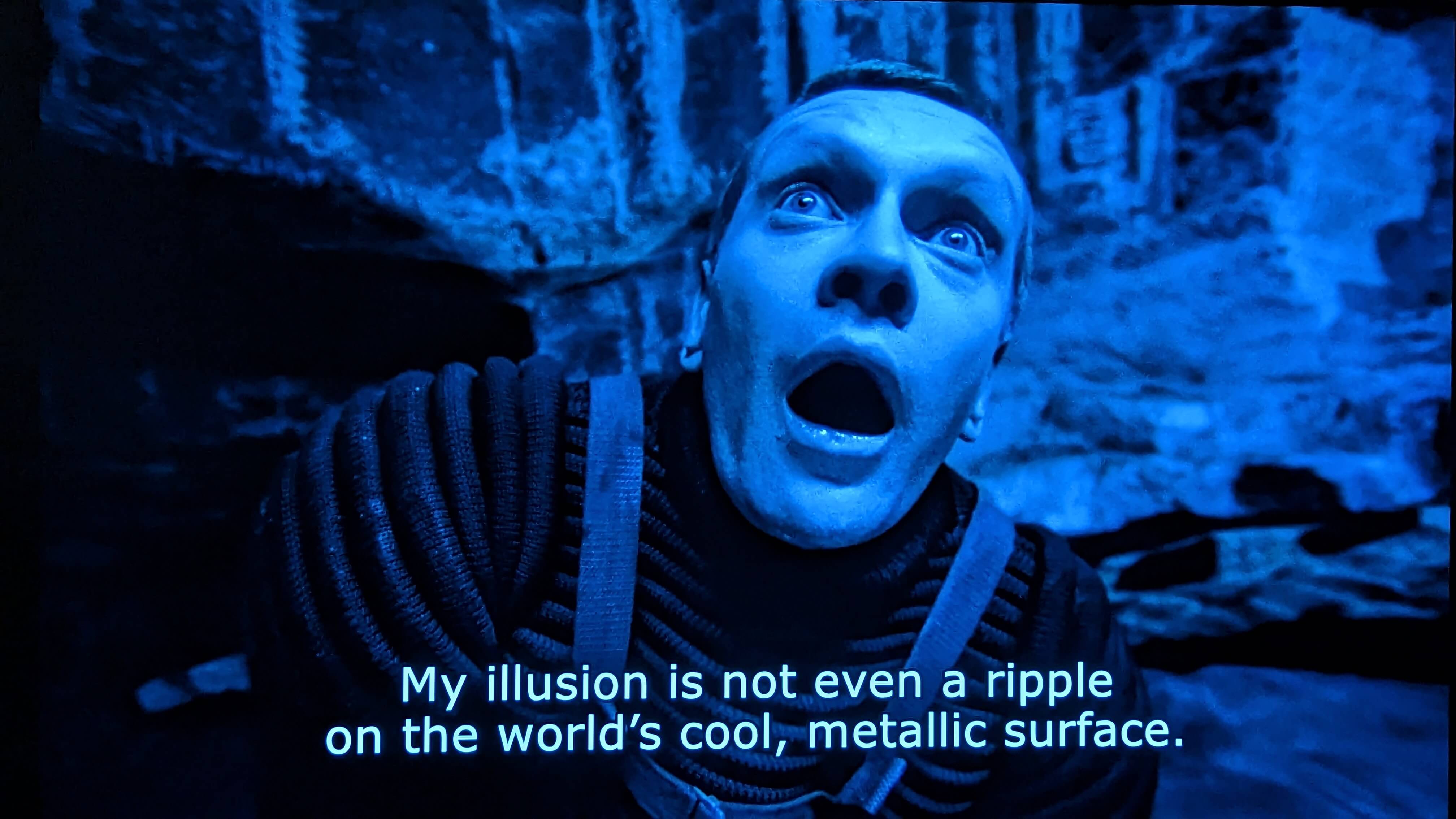

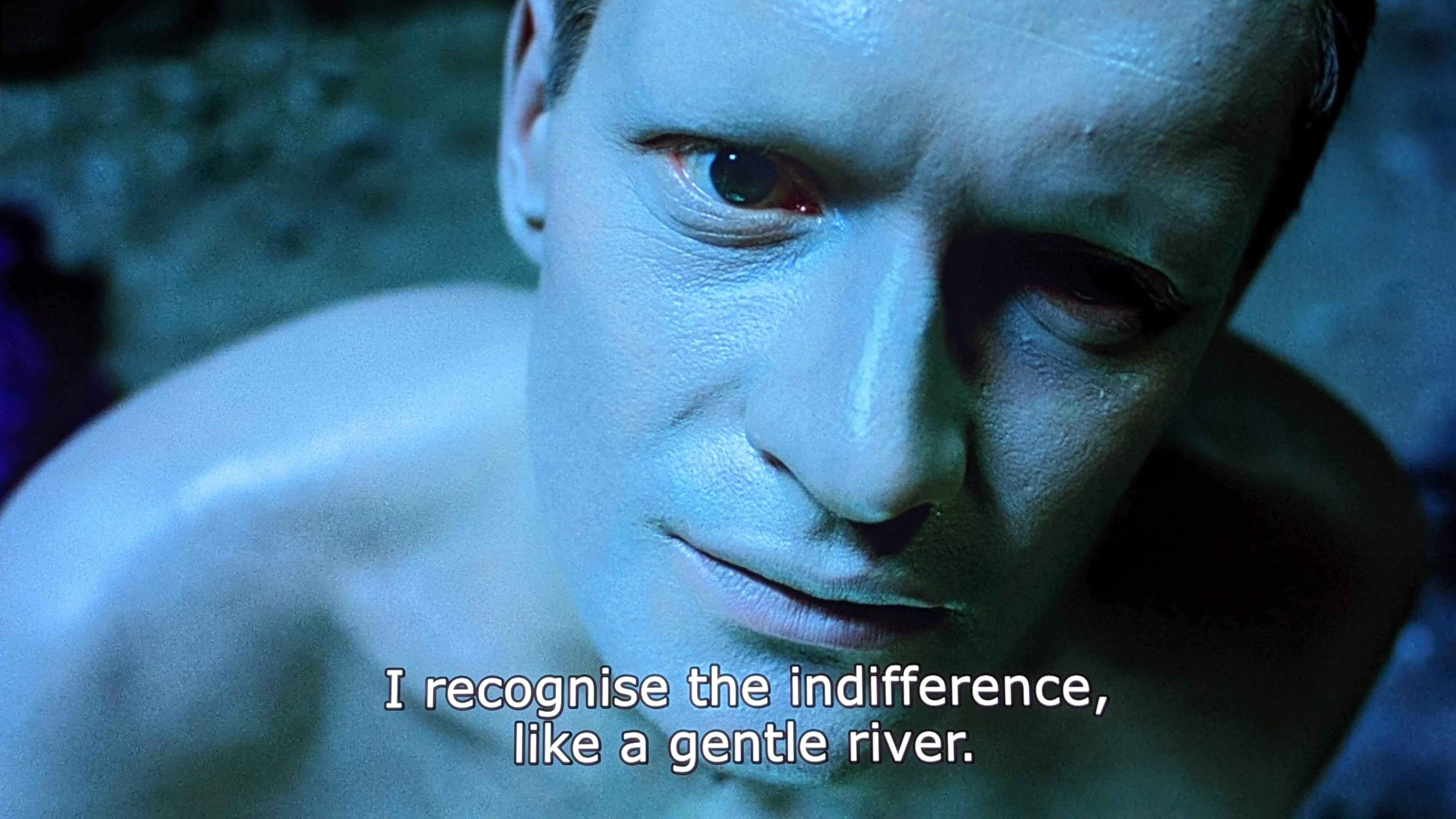

Elements of Jerzy Żuławski’s philosophical influences — Spinoza, Schopenhauer, Nietzsche and Gnosticism — thread throughout the film. Imagery and dialogue are exceptionally aphoristic as if one could pause on any frame and meditate on its enigmatic meaning. Its complex, if not confusing, use of symbolism, fragmented scenes, and delirious dialogue encourage active interpretation by the audience within its broader philosophical context, largely the question of suffering and despair in a chaotic and indifferent universe; a universe that echoes the drifting quality of Schopenhauer’s cosmic pessimism.

The philosopher Gilles Deleuze, known for his work on cinema, once said philosophy should be a kind of science fiction.12 Using the film and trilogy as a vehicle with Deleuze as our guide, we can explore the role art and cinema play in both constructing and deconstructing worlds. How do we respond to failed utopias and ecological devastation? Through joy and positive affect (Spinoza) or acknowledging limits, loss and destitution (Schopenhauer)? Having evolved out of his reading of Spinoza and Nietzsche, how vital is Deleuze’s vital materialism in an age of coming impoverishment?

The Conqueror

“Being subject to external influences, a person exposes himself to what is favorable and unfavorable to him. His whole life is like the rocking of a fragile boat on a stormy sea; a person is stirred by hatred and love, and animated by hope, and once again he is overwhelmed by despair. His life passes amidst eternal uncertainty. Man, driven by the necessity of his innate rights, stands head to head to fight against external circumstances, unarmed and supported by nothing, and therefore he can only win if, by chance, his essence has more strength than the external influence opposing it. And even in the most favorable cases, when the outcome of the fight is in his favor, he gains only a low, almost animal degree of perfection.” —Jerzy Żuławski

A lunar sea is all that separates the colony from the ancient civilization of the Sherns. Characters in the film frequently reference water as a metaphor for spiritual oneness. Many European philosophers — Spinoza, Schopenhauer, Nietzsche — compared life to a boat adrift at sea. Spinoza would say, that reason, aligned with conatus, could steady and steer that boat. Schopenhauer, however, was skeptical of reason’s power to redeem. We are too often overwhelmed by an irrational will. Existence involves encounters with outside forces that are experienced sometimes as separate from us or as an alien power from within. There is a limit where the origin and complexity of our affects and relations eclipse comprehension, and the noumena remain unintelligible, or even arcane and Lovecraftian in their obscure power to effect us. These allusions to undifferentiated oneness (like Freud’s “oceanic feeling”) rather than referring to some mystical transcendence where identity is somehow preserved in unity with the beyond, may refer instead to the dissolution of self into the immanent flows of life.

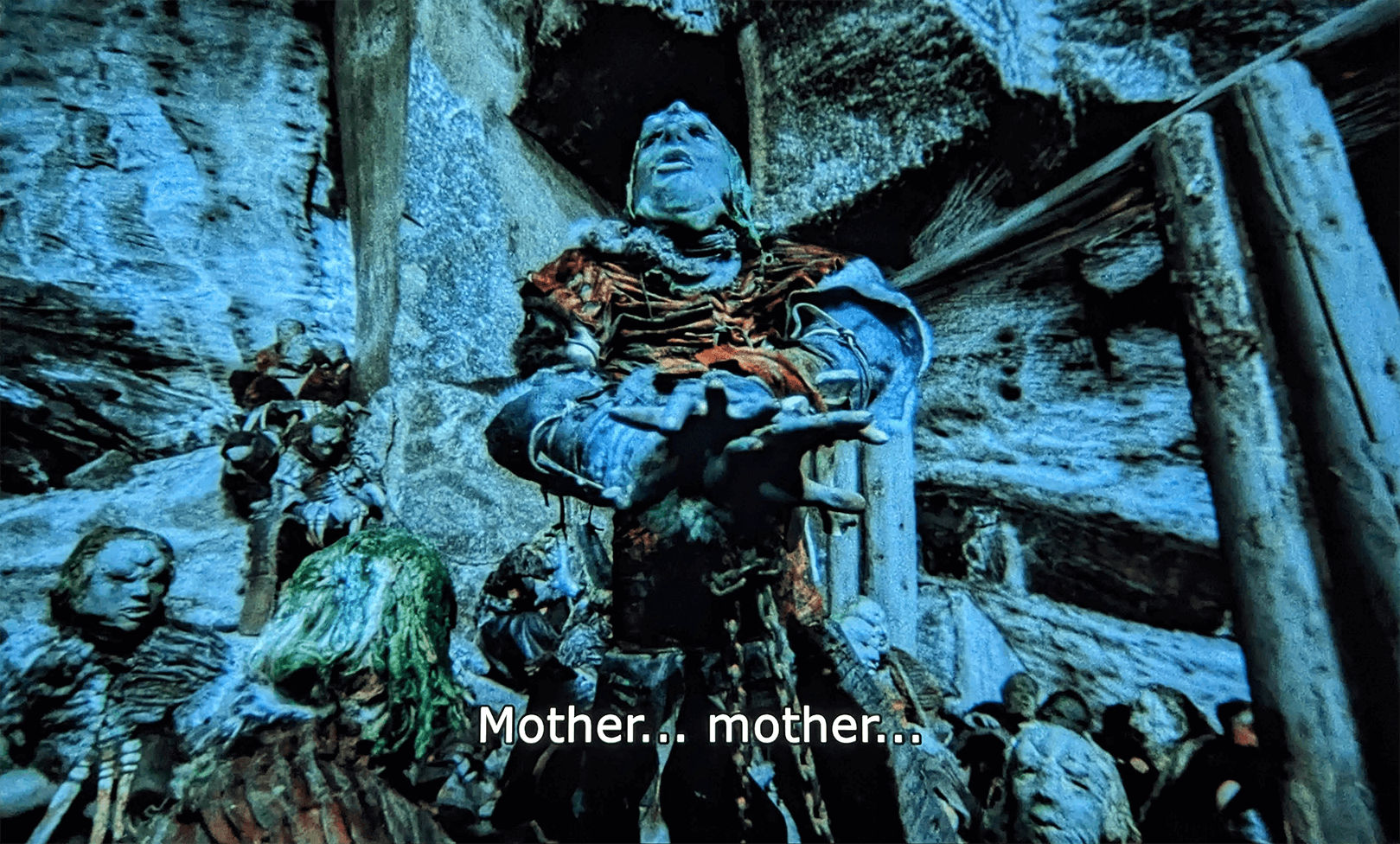

After generations at war with the Sherns, the colony is driven deep into the underground of the Silver Globe, recalling the chthonic, subterranean depths of the unconscious rather than the lofty mountain peaks of the intellect. Marek is the first astronaut to arrive from Earth since the founding expedition. He becomes hostage to the colony’s ignorance and fears who claim he is the messiah that will conquer the Sherns. He doubts his divinity but takes advantage of his position of power.

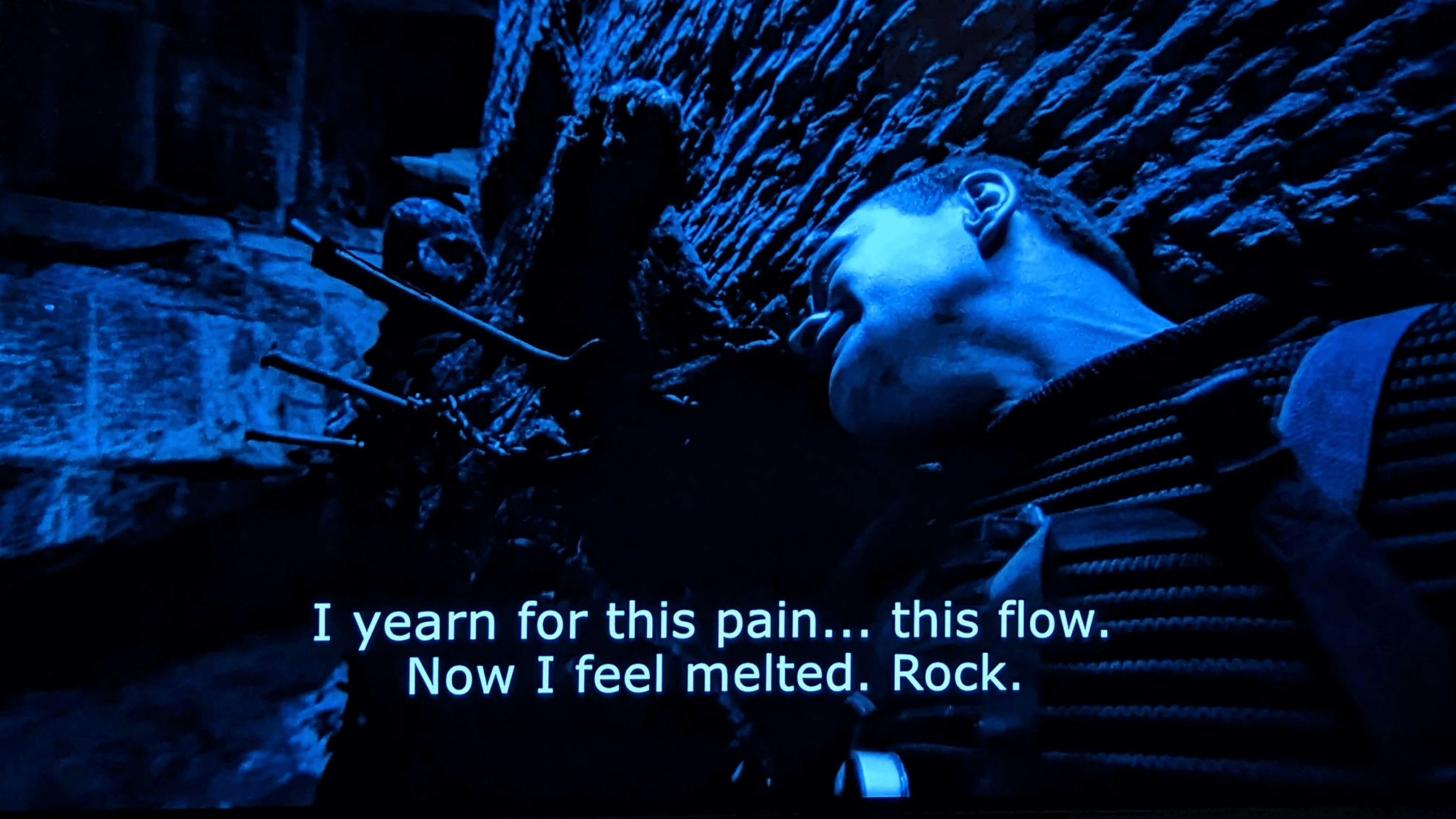

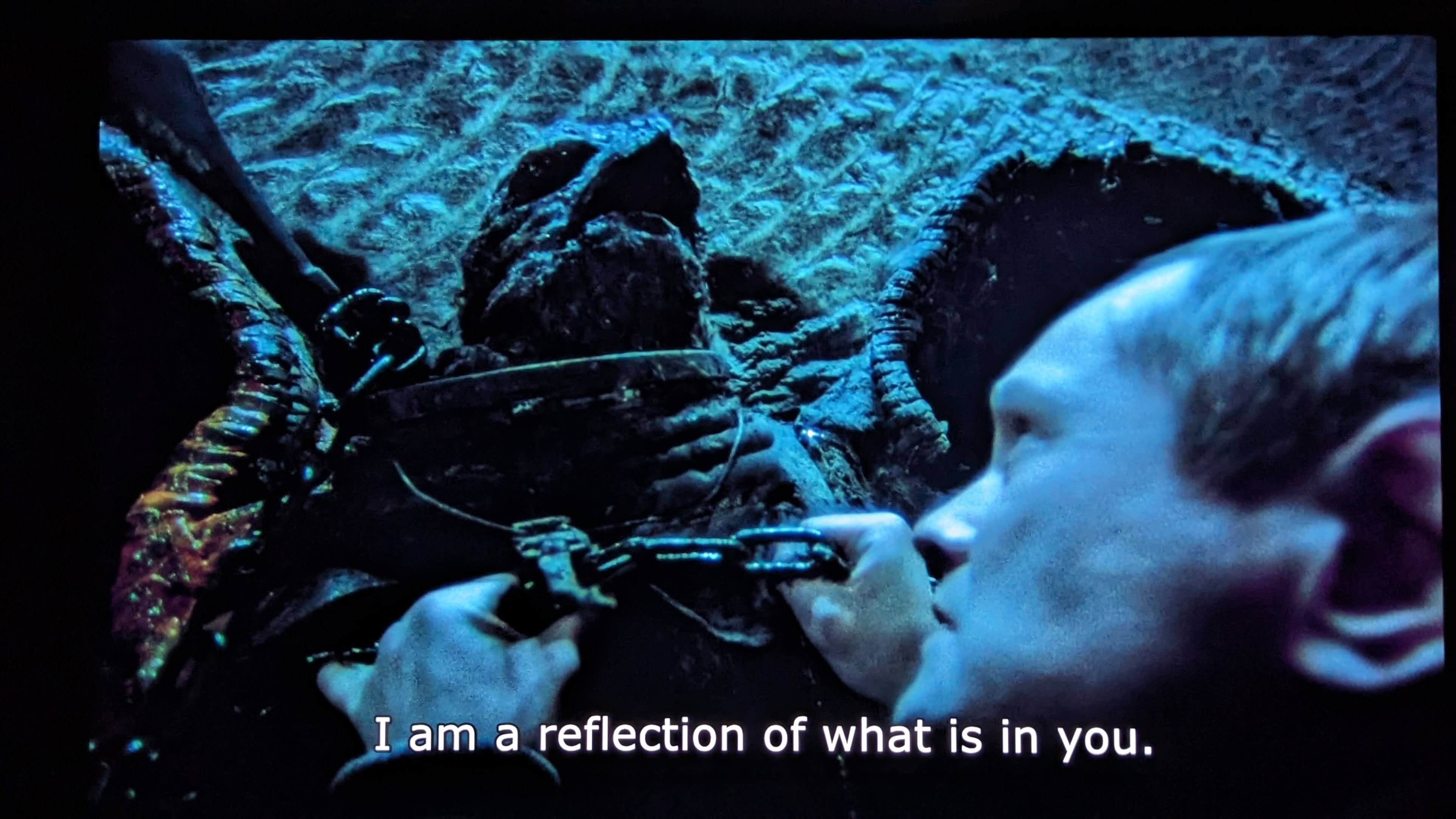

Marek captures and interrogates Aviy the Shern, a dark and uncanny anthropomorphic, sculpture-like figure, more reminiscent of a muddy, seaweed-dripping geological formation than a living being. The Shern is a highly intelligent, demonic or angelic figure indigenous to the planet that speaks as if it is the voice of the Silver Globe itself. The telepathic Shern is a mirror into Marek’s psychic struggle between his human “divinity” and baser, animal instincts, reminiscent of the tension between spirit and body in Jerzy Żuławski’s synthetic monism. Marek finds himself telepathically flooded with the incomprehensible workings of the cosmos (or at least deceived by the Shern into believing so; short-circuiting Marek’s desire with excess information may be its secret weapon). The Shern claims it is “at one with itself” and only reflects Marek’s fractured humanity. In a hysterical breakdown of phantasmatic lunacy, split between sublime ecstasy and horror, Marek is nothing more than a tiny mercurial drop in a vast silvery ocean, at the mercy of the planetary forces (embodied by the Shern) that both constitute and threaten to destroy him. The conquerer is tested: either he integrates the transformative forces that emerge from the encounter or risks being subsumed by the Silver Globe.

Like Schopenhauer, perhaps it’s not fear of death and that torments Marek as much as it is the dread of life. Bound to a wheel of perpetual desire and suffering, as Schopenhauer suggested, one develops a longing for its cessation. Just as Spinoza denounces the moralist trinity, Nietzsche critiques the ascetic ideal, including Schopenhauer’s, as a nihilistic denial of life. In spite of all life being tragedy, Nietzsche’s Dionysian pessimism seeks to joyously affirm it. Nietzsche’s will to power is in ways similar to Spinoza’s conatus but more expansive and transformative. At least in the somewhat contentious tradition of French Nietzscheanism (Bataille, Klossowski, Deleuze), the will to power is an active, life-affirming drive, one of not just preservation but of self-overcoming and the creation of new forms of life and thought. Where Schopenhauer sees the negation of the will, the ascetic rejection of desire, as a path to mitigate suffering, Nietzsche embraces the will to power as an essential aspect of human vitality and creativity.

While Nietzsche is often appropriated by the political right, and understandably criticized by the political left for espousing antiquity-inspired aristocratic privilege, in Nietzsche and Philosophy (1962), Deleuze intentionally coopts and systematizes the existential, vitalist and antagonistic aspects he finds in Nietzsche’s thought out of which any politics can arise. Nietzsche always asks, “Who is speaking?”, challenging the hidden interests and biases of those who make claims to absolute truth without acknowledging the limits of perspective and interpretation. As Deleuze points out, in a way similar to Spinoza, Nietzsche’s radical contribution to philosophy is in foregrounding how no values are given to us; we continuously create them. In both Schopenhauer’s and Nietzsche’s philosophy, the term will, unfortunately, suggests an individual act of agency (e.g. willpower). However, the will to power was never simply about power conflicts between individuals. Instead, especially by way of Deleuze, it becomes a metaphysics of intensities or relational forces. Active forces do not, in essence, deny or negate that which they are not, but affirm their own difference. Nietzschean overcoming is not about dominating others — which is a reactive force of the lowest power — but navigating reactive forces and conquering one’s own ressentiment. Actively affirming one’s fate in life, amor fati, is the vital antidote to nihilism.13

“Is it only the animal in you that is alive? What about that which lives through that animal?” probes the Shern. Marek writhes in response, identifying first as the Shern, then as flows of “melted rock”, the “inhuman transparency” of water, the “motion of the will”. The encounter can be read as one of schizophrenization — as articulated philosophically (not clinically) by Deleuze and Guattari — a limit-experience of singularization before individuation, when the chaosmos of forces and potentials suffuse identity.14 Defined by mutable relations, fluid thresholds and permeable boundaries, the schizo shifts perspectives from one singularity to the next, free of any Oedipal triangulation. Reminiscent of Artaud — “I, Antonin Artaud, am my son, my father, my mother, and myself”11 — Marek stutters at the limit of language, “when the language system is so much strained, language suffers a pressure that delivers it to silence.”15

In becoming-Shern, Marek enters into a desert-like zone of indiscernibility. It is uncertain where one multiplicity ends and another begins. The unconscious itself isn’t isolated to any individual but a social field in constant exchange, a communication of unconsciouses — dreams, memories, repressions.14 The encounter doesn’t converge into something familiar but unfolds into uncharted territory, a becoming of surplus affects, unrecognizable as wholly Marek or Shern. Marek’s dark revelation is that he is nothing but an opening onto chaos, a torrent of creative and destructive forces that exceed his individuation. His psychic mis/communication with the Shern does not lead to enlightenment or power, but a deeper dehiscence (the splitting or bursting open of a wound), subsumed by the will of the Silver Globe.

Overwhelmed by the Shern, Marek proclaims it is God before being shaken to his senses by Marta (the role of women in Żuławski’s films is a whole other controversy). In a fit of animalistic or “all-too-human” violence, first towards Marta then the Shern, Marek bashes the Shern over the head with a rock, ending the psychic combat.

In the end, Marek is bested by his own sad passions and those of the colony, due to his inability to conquer the alien within and integrate the gnostic shock of the Shern, or more practically, from being unable to escape the greater, contingent forces of history and politics that undermine him. The conqueror is not a historical inevitability or divine superman, but a failed collective enterprise. Mirroring the fate of Christ in the New Testament, Marek is deemed a false messiah and condemned to die. His ultimate freedom from human bondage is his brutal crucifixion, soaring above a cyanic-blue sea, vibrant red blood dripping into the grey, lifeless desert below, becoming one with the Silver Globe.

There is an “ineliminable violence”16 intrinsic to life. It is this dissonance and monstrosity at the dark heart of thought and existence that drives Żuławski’s films.

What Can Cinema Do?

“We do not even know what a body is capable of.” — Spinoza, Ethics

For Deleuze, philosophers like Spinoza, Nietzsche (via Schopenhauer), and Artaud foregrounded the body as an alternative to the modern, rational subject as the dominant model of thought since the Enlightenment. Existence is becoming, always in motion, a dynamic flux of forces, processes and relations, characterized by all the current catchwords in contemporary theory: multiplicities, entanglements, assemblages, metastabilities. There are no fixed essences; no originary model or blueprint. As Karen Barad has summarized succinctly: “relata do not precede relations.”17 Territories are defined by their boundaries; forces by their results; terms in relation to context; thought by the problems it encounters.

There is no essential human nature; only what a body can do. It is not what a body is, but its capacity to act that defines its being. Mind is a kind of body, in so far as Spinoza’s unified theory considers all “human actions and appetites just as if it were a question of lines, planes, and bodies.”5 Conative bodies enhance their power to act by forming alliances within an ecology of other bodies. Active states, often accompanied by joyful affects, express productive interactions, while passive states, tied to sad passions, inhibit agency.

Especially with a film like On The Silver Globe, viewers are not merely spectators but active participants in co-creating the cinematic experience. In Melancholy Emotion in Contemporary Cinema (2019), Francesco Sticchi outlines a Spinozist analysis of film, foregrounding Spinoza’s emphasis on activity and interaction to challenge conventional notions of passive viewership.18 Leveraging Deleuze’s work on cinema, Sticchi considers how cinema (reminiscent of Artaud’s Theatre of Cruelty) engages viewers pre-cognitively. The function of cinema isn’t just representational; it immerses and transforms the viewer’s cognitive and emotional faculties by manipulating our sensory-motor schema with audiovisual affects. Cinematic images are composed of percepts or blocs of sensation, which act as the pre-representational building blocks of thought.19 Deleuze’s movement-image and time-image illustrate this, with the former driving narrative momentum and the latter enriching contemplative and emotional engagement. In provoking thought and evoking emotion — joy, melancholy, trauma — cinema offers a potential encounter with problems outside life’s routine, broadening what a body can experience, understand, and act upon.18

Reflecting on our relationships and the true causes of our emotions through film can transform even negative emotions into empowering joy. It could be anger toward a villain or perceived injustice, or simply the enjoyment of the aesthetic dimensions of a film, cinema’s power to affect is an initial step toward action. If we are to live ethically, cultivating an appropriate affective mood or landscape is crucial.20 Through emotional engagement, cinema uniquely opens us up to being affected, enhancing our capacity to act in the world, leading to deeper ethical involvement.18

In On The Silver Globe, we share the protagonists’ trauma and existential uncertainties. Even if alienated from the characters by the intense and fragmented dialogue in an unfamiliar world, we are at least viscerally struck by the image. In vividly depicting how sad passions enable social toxicity, the film challenges us to confront destructive and nihilistic tendencies within ourselves. Free from any conventional narrative structure that resolves in moral judgment or a happy ending, meaning is left open to interpretation, resonating with Spinoza’s understanding of ethics as active interpretation, a question of encounters rather than the passive acceptance of some prescriptive morality. Wisdom comes from exploring what we are capable of, what one can do, not must do in duty to some moral imperative.6

“Ethics is a typology of immanent modes of existence, we can’t refer it to some system of values that’s imposed from outside, it has to be navigated and negotiated through lived experience, both individual and collective.” —Deleuze, Spinoza: Practical Philosophy

Cinema has the unique capacity to render visible the relational nature of human experience. Żuławski made films during a time many filmmakers believed in cinema’s potential to effect profound spiritual and social transformation, to become not just another moral tale, but a shared ritual and visionary revelation. In exploring these themes, not only thematically but in undergoing extreme production challenges and experimenting with the formal aspects of filmmaking, On The Silver Globe was an answer to Spinoza’s challenge in asking what can a body do?

What can cinema do? Can it enact the sacred? Can it be a catalyst for transformative thought and action? Can it be a form of resistance?

“We must revive the concept of an integral show. The problem is to express it, spatially nourish and furnish it, like tap holes drilled into a flat wall of rock, suddenly generating geysers and bouquets of stone.” —Artaud, The Theatre and its Double

Machinic Phylum

“At the limit, there is a single phylogenetic lineage, a single machinic phylum, ideally continuous: the flow of matter-movement, the flow of matter in continuous variation, conveying singularities and traits of expression.” —Deleuze & Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus

Resembling a Spinozist monism, thought and extension form a composite unity across the machinic phylum, a lineage of transversal forces that introduce change and disruption. All forms of matter-energy are expressions of an underlying network of flows that elude our accustomed binaries: organic/inorganic, living/nonliving, human/nonhuman, subject/object, and so on. Deleuze and Guattari were machinic materialists. All of existence, including consciousness and matter, can be understood as dynamic assemblages shaped by machinic (not mechanistic) processes of transformation. Matter itself is inherently active, creative and autopoietic, expressing a vitalist force like Spinoza’s conatus or Bergson’s élan vital. Rather than a hylomorphic model where form transcends matter and is imposed externally, the genesis of form is morphogenetic, emerging through its own immanent processes in the flow of matter-energy.21 Though, importantly, this vitalism is not without counter-tendencies toward the chaotic and entropic.

In Vibrant Matter (2010), Jane Bennett emphasizes the active vitalism of matter, challenging prevalent life-matter binaries where the organic is often privileged over the inorganic as possessing life and agency. While remaining steadfastly materialist in her analysis, Bennet draws heavily on Spinoza’s conatus and Deleuze and Guattari’s vital materialism to argue that the inorganic, while not fused with any kind of immaterial or divine-like spirit, exhibits a degree of agency, a capacity for affecting and being affected that is characterized by dynamic self-organization and emergent complexity. By thinking about matter as vibrant, Bennett advocates for a more inclusive understanding of environmental ethics, emphasizing the significance of reciprocal relationships between humans and nonhuman materials that may be more like us than we think.20

Recalling Marek’s psychic encounter with the Shern, there are geophilosophical processes that both constitute and threaten our existence, manifested as very this-wordly (not other-worldly, yet nevertheless sacred) things, revealing our immanent relationships with and inextricable reliance on inhuman forces that seemingly possess a mind of their own.

“Thoughts of lead, of nothing, of lead. The lead cancer consuming my body, fluid as an amoeba.” —Marek, On The Silver Globe

Metals are especially expressive of a nonorganic vitalism, the order and complexity of their polycrystalline lattices expressing a proto-organic vibrancy full of intensities and affective energy. Even Schopenhauer, in one of his weirder moments, says “this matter, now lying there as dust and ashes, will soon form into crystals when dissolved in water; it will shine as metal; it will then emit electric sparks.”7 Even organisms, such as ourselves, emerge from the biogeochemical cycles of the earth. As geochemist Vladimir Vernadsky said, “We are walking, talking minerals.”20 Deleuze and Guattari describe metallurgy as a conductor of both material processes and immaterial practices, experimenting with new forms based on the potentialities inherent in matter-energy. Unlike the scientist, the craftsperson or artisan is less interested in what a metal is than what it can do.21

“What metal and metallurgy bring to light is a life proper to matter, a vital state of matter as such, a material vitalism that doubtless exists everywhere but is ordinarily hidden or covered, rendered unrecognizable.” —Deleuze & Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus

In The Filmmaker as Metallurgist (2016) Patricia Pisters equates political filmmakers with metallurgists, emphasizing that it is not a metaphor, but a literal equivalency in their manipulation of tangible materials and ideas. From the silver used in film chemicals to the liquid mercury used in fluorescent lighting and liquid crystal displays, to the coltan in our capacitors, there is a technological and geophilosophical lineage in film “from the earth to our screens.” Like metallurgists, political filmmakers work across creative and political disciplines by mining and editing archival footage, innovating technological processes, and making artistic choices that forge historical narratives and shape collective memory.22

Throughout On The Silver Globe there are frequent references to metal sought by the colony as the raw material for war and key to the mysterious, technologically advanced (and seemingly magical) artifacts brought from Earth by the astronauts. It is interesting to note Żuławski was a fan of artists like Jean Giraud (Moebius) and Enki Bilal who were frequently featured in the popular 1970s French SF comic anthology Métal hurlant (Howling Metal), whose work might have inspired some of the creative vision for the film.

In crafting On The Silver Globe, Żuławski, cinematographer Andrzej Jaroszewicz, and their crew experimented with the creative alchemy of film materiality, shaping the movie through the constraints and potentials of its materials. Wanting to depict a truly other-worldly look of an alien planet with unusual chemical composition, they employed high-temperature film stock that emphasized blues and added filters typically used in black and white photography for a monochromatic image effect, giving the film its characteristic cyanic blue and porcelain sheen (Żuławski said he wanted to reproduce the look of a Japanese Geisha doll). Manipulation of analog source material was an intentional choice that would make post- production alterations (often imposed by reviewers aligned with state propaganda) impossible. 10 Through this process emerged an aesthetic in which the materials themselves had a say.

Also worth noting, where art and technological innovation meet, that Mieczysław Bekker heavily referenced Jerzy Żuławski’s descriptions of his lunar vehicle, and together with NASA illustrators, created the initial designs of what would later become the actual Lunar Roving Vehicle used in the Apollo missions.2

It may seem overly scholastic to use a term like machinic phylum to say “film is made with stuff” but there is significance in highlighting how art and technology are shaped by creativity inherent in materials themselves. The filmmaker’s task is to “harness unthinkable, invisible, nonsonorous forces”21 evident through the manipulation of materials; not to represent reality as it already appears. A film is a complex assemblage of images, sounds, editing, performance, narrative conventions, cultural context, audience expectations, etc. The introduction of new filmmaking techniques changes how stories are told and how audiences experience them, acting as machines that shape the cinematic assemblage. In tandem with an artist’s creativity and personal history, and broader social, historical, and economic conditions, material forces shape what cinema can do. Art, especially cinema, understood as Deleuze’s cinematographic concepts of movement-image and time-image, can act directly on the materiality of consciousness. Political cinema can be an apparatus to affect thought, incite action and disrupt prevailing narratives and social structures. It is what Deleuze and Guattari called a war machine.22

Cinematic War Machine

“To place thought in an immediate relation with the outside, with the forces of the outside, in short to make thought a war machine … this is its sole and veritable positive object (nomos). Make the desert, the steppe, grow.” —Deleuze & Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus

Cinematographer Andrzej Jaroszewicz, an athlete as a young man, was the “intelligent eye” behind the subjective, hand-held camera work meant to emulate the astronaut’s body cam. On The Silver Globe was an early film to first employ such an unusual technique for a significant portion of the film. The camera was likely an Arriflex 35, relatively lightweight and portable for its time, but still heavy. Its reflex viewfinder allowed filmmakers to see through the lens directly, giving them a more accurate representation of the final shot which enabled more dynamic cinematography and heavily influenced the evolution of film aesthetics. The antithesis to the slow rhythm of Tarkovsky’s “sculpting in time”, the spontaneous camera work and non-linear editing lend the film a temporal dynamism more reminiscent of Dadaist collage and Soviet Montage than calculated sculpture, conjuring a sense of delirium that echoes the intensity and fragmentation of the colony as a “crazy bunch of shouters”23 spewing bits of philosophy at one another. Shot like a war documentary in constant motion yet always managing to come to rest on almost painterly compositions, the crew joked Jaroszewicz was a “living image stabilizer”.2 Exercising his body so that he could keep his balance just like village women he had observed carrying jugs of water on their heads,2 Jaroszewicz took up Spinoza’s challenge literally: what can a body do? In becoming-camera, pushing human capacity to the limit in relation to the mechanics of the camera, Jaroszewicz’s work results in a unique visual language that speaks to the relationship between human and machine in the creative process.

Zulawski on set, photo by Stefan Kurzyp, source: FINA Fototeka

Zulawski on set, photo by Stefan Kurzyp, source: FINA Fototeka

Film production was suspended in 1977 by the Polish vice-minister of cultural affairs, citing “exceptionally low work efficiency and overpricing.”24 The old adage “time is money” is what Deleuze called “the old curse which undermines the cinema.”19 It is suggested the decision was partly a personal vendetta against the Żuławski family and “a demonstrative attack on the film community, a show of strength towards filmmakers who were becoming more and more willing and aggressive to join the public debate.”24 While a science fiction film and oblique as political cinema per say, On The Silver Globe was very much a political film that irritated the establishment.

Almost a decade after the film’s suspension, Żuławski revisited the archived footage and edited in scenes of contemporary Poland with narration to patch what had been left unfinished, expanding on an epic that had begun decades earlier with his great uncle. Żuławski, Jaroszewicz and their crew fused disparate material and temporal flows to shape the final film. As an analogy of Poland’s historical struggle for independence, it is a work of political cinema that attempted to alter the dominant representation of history and imbue it with new emotional and affective dimensions, exemplifying Pister’s connection between filmmaking and metallurgy. As a cinematic war machine, it broke new, “desert” ground for creative expression and the imaginative horizons of cinema outside limitations dictated by the state.

Is it privileged or naive to believe in art or philosophy as resistance in a war torn world? Or is the very purpose of art, as Deleuze says, “to free life from what imprisons it,”25 to render visible those forces that have captured life.

A Stubborn Crystal

Free of metaphor and myth, he grinds

a stubborn crystal: the infinite

map of the One who is all His stars.

—Jorge Luis Borges, Spinoza

A lens grinder by trade, Spinoza was a craftsman and artisan, spending many hours meticulously polishing glass, crafting optical material conforming to precise mathematical calculations used in telescopes and microscopes to enhance vision. As he aided people in seeing the physical world more clearly, his philosophy, geometric in its method, helped in understanding our conceptual one. Deleuze calls it a “radical enterprise of demystification”6 that revealed the distortions of our irrationality. By participating in a non-philosophical craft, Spinoza was grounded in the material, tangible aspects of the physical world and everyday life. Rather than the detached and abstract pursuit of a totalizing theoretical system, Spinoza’s philosophy was a practical investigation of life.

“The geometric method, the profession of polishing lenses, and the life of Spinoza should be understood as constituting a whole. For Spinoza is one of the vivanis-voyants (living-seeing). He expresses this precisely when he says that demonstrations are ‘the eyes of the mind.’ He is referring to the third eye, which enables one to see life beyond all false appearances, passions, and deaths.” —Deleuze, Spinoza: Practical Philosophy

Spinoza didn’t just examine the manifestations of religion, including its practices, dogmas, and effects on society; he also sought to understand the foundational mechanisms of human experience that lead to religious phenomena — the laws of its production. For this he was ostracized and excommunicated from the religious community. Published anonymously in 1670, Tractatus Theologico-Politicus was deemed “a book forged in hell” and added to the list of books forbidden by the Catholic Church.6

“A humanity bent on self-destruction, multiplying the cults of death […] Always busy running life into the ground, mutilating it, killing it outright or by degrees, overlaying it or suffocating it with laws, properties, duties, empires — this is what Spinoza diagnoses in the world, this betrayal of the universe and of mankind.” —Deleuze, Spinoza: Practical Philosophy

Similar to Spinoza’s resistance through philosophy, and in the tradition of his great uncle Jerzy, Andrzej Żuławski arguably believed in the critique of power structures through fiction as a means of resistance against the corruption of church and state. But rather than thinking in terms of philosophical concepts, artists think in creative combinations of percepts and affects. Filmmakers think with images.26

Philosophizing through filmmaking, Żuławski focused his cinematic lens on the desires and delusions of humanity from the cosmic perspective of eternity. He considered On The Silver Globe a deeply personal journey, possibly mirroring that of a gnostic or alchemical practice, undertaken during a depressive period in his life of personal struggle and failed relationships; yet one of exceptional creative vigor. The crew, to this day, recalls the formidable challenges faced during production, but also the unprecedented creative energy that came with the knowledge they were all contributing to something visionary.24

While celebrated for its daring experimentation, its eventual reception at Cannes in 1988 was mostly ambivalent. Still today, it remains largely a cult film, its avant-garde style overshadowing its broader appeal, serving as a reminder of the challenges in translating visionary ideas into a coherent narrative that resonates with a broader audience, especially under material constraints and risk of censorship (as was Spinoza). That said, it stands as a testament to the potential of film as an act of resistance, not only in the content of the film but in its formal aspects and the filmmaking process itself. Cinema is not merely a representational practice but a world-making one, that through aesthetics and affect can influence ethics as much as words. It is not that there is a world and cinema represents it; worlds are produced cinematically. On The Silver Globe, with its distinctive cinematographic language and material experimentation, exemplifies the transformative potential of cinema to forge new worlds.

“The cinema does not just present images, it surrounds them with a world.” —Deleuze, Cinema II

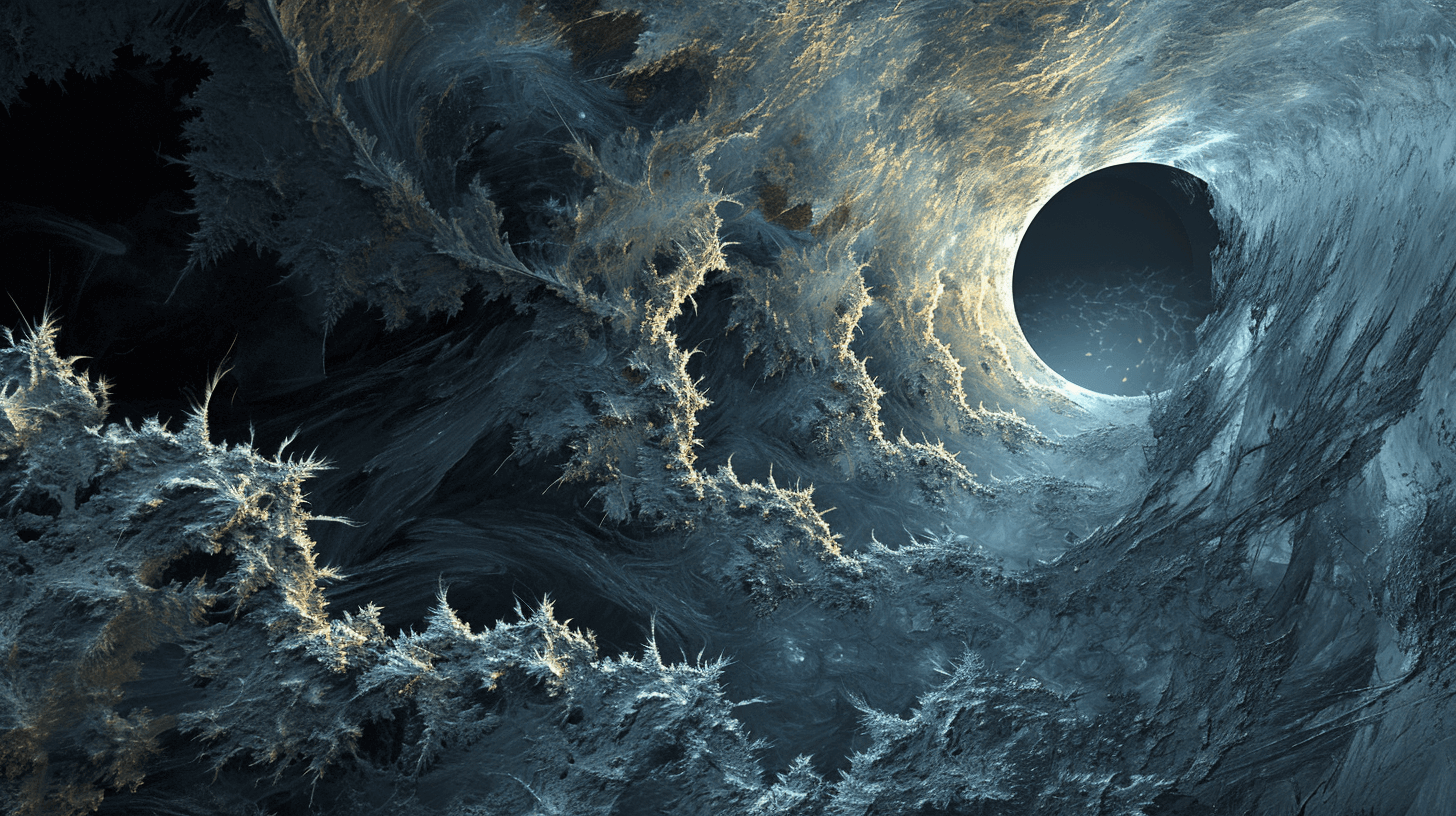

Cinema, for Deleuze, is not about the search for hidden meanings through psychoanalytic and semiological readings; it is to be understood directly, as a composition of pre-conceptual images and signs.19 Deleuze thinks of cinema in terms of time crystals; the interplay of the actual and the virtual, where time folds and splits into non-linear series of events that challenge linear narratives of past, present and future. Cinema “sees” and “thinks” in multiple and varying ways beyond any singular and limited perspective. Following Bergson, all matter-energy is luminous. Before there is mind and world, there are active prisms of relations, each relation itself an image, an interaction of appearances, a perceptual encounter. “The eye is in things, in luminous images in themselves.”19 Life itself is perception and knowledge a stubborn crystal.

Deleuze ends his essay on Spinoza’s life with this quote from Henry Miller:

“You see, to me it seems as though the artists, the scientists, the philosophers were grinding lenses. It’s all a grand preparation for something that never comes off. Someday the lens is going to be perfect and then we’re all going to see clearly, see what a staggering, wonderful, beautiful world it is…” — Henry Miller, Spinoza: Practical Philosophy

Of course, to read Deleuze and Guattari as simply a psychedelic trip through the “kaleidoscopic complexity of the world” is to miss the point.27 Is it that the perfected vision “never comes off” simply from lack of precision? Or does our gaze “curve around an absence,” something imperceptible that escapes the “panoptivision of our relations,”28 in that desire deforms what it sees?

The Lost Earth

“Earth seems to have changed into an open, merciless and cautious eye that is stubbornly staring at us, surprised at our running away from it with our bodies, the first of its children to do so.” —Jerzy Żuławski, The Lunar Trilogy

Żuławski’s film resonates even more today as we collectively grieve in the ongoing event of the Anthropocene. Earth has become a commodity of increasing scarcity. An accelerating and seemingly inexorable libidinal economy ravages the finite resources of the planet and undermines the regenerative possibilities of life on Earth. We are not only the ones destroying life but the ones who will be destroyed. The desert, antithetical to life, is the final destination of our desire, “an eschatological space by which capitalism speculates on its own collapse.”1 Rational exposition too often falls short in helping us grasp the full gravity of the moment. Just having a long list of grievances, injustices and scientific facts too often fails to compel us to act, let alone teach us how to carry the weight of sorrow.

The utopian imagination once envisioned possible futures that could resist and reverse ongoing destruction, asking the question: how will we rebuild? What materials and affects will be needed for the repair? What stories will we tell? But what good are these questions in a time of unmitigable loss and growing certainty there is no future? Reparative narratives may no longer apply in a time of no redemption. We need art and culture that resists denial, apathy and despair; both the logos of rational discourse and a mythos that mobilizes praxis (not in the Sorelian sense of an aestheticized collective narrative, but an ethos that appeals to emotion, irrationalism, and enjoyment). Ecomelancholia, while reflecting genuine grief over environmental loss, risks becoming self-indulgent and counterproductive in dwelling on despair instead of seeking solutions. We need to transform grief into constructive, or deconstructive, engagement.

“Seven hundred and seven lunar days have passed since our Exodus. O Earth! O my lost Earth!” —The Old Man, The Lunar Trilogy

In The Lunar Trilogy, colony members are haunted by the specter of the old earth that hangs over them in the sky like the eye of a vengeful, maternal deity, the origin of their initial transgression, the mother they left and the Eden they sought in vain to outshine. Given a habitable oasis on a desert moon with infinite possibilities to create humanity anew, no one had the will to do it. And now Earth, itself in ruin, is threatened with destruction by an apocalyptic weapon that will “wrench the Earth from its orbit,”23 like Nietzsche’s Earth unchained from the Sun. In the final book, The Old Earth, a celebrated physicist echoes Schopenhauer’s rational pessimism, lamenting the impossibility of utopia.

“Any harmony is an artificial, invented concept. In nature, in the universe and human society, there is only struggle and the passing seeming balance of opposing forces … After all, it does not matter if the people or the tyrant rule, the chosen sages, or a crazy bunch of shouters. There will always be someone oppressed, someone who is always unhappy, there will always be some harm done. Someone will always suffer.”23

The scientist bemoans that the material universe is in fact “nothing”, quotes Heraclitus’ phanta rei, waxes poetic about the entropic heat-death of the universe, and then berates both the rich and the mob. Far from a celebration of the miracles of technology and fantasies of interplanetary colonization, the promise of scientific and technological progress is suspect amidst such spiritual impoverishment:

“Vanity of vanity! Inventions, discoveries, benefits, and amenities are used primarily by those who are well-off even without them, and who are the least worthy in the community: the vast majority of whom are, lazy and thoughtless. Inventions only enhance these advantages of the mob.”23

Another character, Nyanatiloka, a spiritual ascetic, personifies what Schopenhauer described as one who “gazes back calmly at the phantasm of this world.”7

“I live in the most perfect form … personal and all-encompassing. It is possible because I learned to connect with the world and its spirit in the true unity, like it was at the beginning, before human consciousness was conceived. I do not need to look at flowering meadows, listen to the roaring sea and the storm because I myself am truly a growing land and a flower, and a river, and a tree, a wind, and a sea. I feel the harmony in the pulse of my blood and in the rhythm of my thought. And it is at its deepest level, hidden under a delusional phenomena, under what seems evil, unjust, or unnecessary to a man taken out of the world.”23

Typical of modernist romance, Żuławski’s novel is preoccupied with what Max Weber called the “progressive disenchantment of the world”, the nostalgic longing for a sense of wonder devalued amidst increasing rationality and secularization. Nyanatiloka speaks of a time of unity hidden behind “delusional phenomena” when subjectivity was more “porous” and in deeper engagement and harmony with nature from which it has become alienated, the enchanted pre-modern world we have lost.

In contemporary Deleuze and Guattari inspired new materialism — from Latour’s actor-network theory and Stengers’ animism to Bennett’s vibrant materialism and Barad’s agential realism — there is a move to dereify and reenchant the world as events or entanglements with agency. All of existence is embued with life, relationality, even an animist or panpsychic consciousness, that was once claimed by philosophy as the exclusive domain of human subjectivity. Matter and meaning coincide. As an ethics of repair, it is an admirable move meant to inspire us to recognize all things as worthy of those relationships we usually preserve only for ourselves, such as love, care, responsibility and justice. However, while philosophies of affect and connectivity claim to challenge the harmful exclusivity of universal categories of “humanity” and resist environmental degradation, arguably they can in ways feed into the anthropocentrism and harmful logic at the heart of capitalist extraction and exploitation. Spinoza-inspired monism perhaps obscures important distinctions between nonhuman processes and uniquely destructive modes of capitalist production. Affective materialism - this capacity for vibrant objects, bodies, and materials to enchant and evoke pleasure — may only facilitate the Promethean thinking that everything is a mere means to our own ends, that we can endlessly manipulate and control nature for own benefit, aligning with capitalism’s inherent drive for growth and expansion.2930

Capitalism, in the analysis of Deleuze and Guattari, is a proliferating network repeatedly producing toward and displacing its own interior limits. Through continuous disruption and innovation it undoes and reconfigures existing structures with a single axiomatic imperative: to grow, and to grow increasingly. In doing so, it either assimilates or crushes any alternative, noneconomic ways of living. Rather than maintain order, it manages disorder. Crises, conflicts and failures just add fuel to the fire. Capitalism manufactures desires, generating new ways to please, more materials and experiences to liquidate into capital, more space to enclose, more people to displace, more ways to structure past and future time according to its own logic. It endlessly commodifies, unearthing new frontiers from which to exploit social connections and extract surplus value, breeding competition over cooperation, increasing social inequality and privatizing wealth in the hands of the few. It thrives on connections and the assembly chains of novelty. Inside a global technocracy increasingly online, we arguably have too much connectivity, too much communication, too much visibility and transparency, all wired into an invisible grid of automating, surveilling and subjugating algorithms. Commodity fetishism “enchants enchants enchants” to no end. Anything can be given a face, a voice, made more appealing, relatable, and commodifiable. Even when knowing the true cause of our desires, there appears to be no escape from capital’s demand to endlessly produce, consume and accumulate, often with an obligatory and sadistic optics of positivity that’s necessary just to survive. Servants with a smile.

“Today is not the age of sad passions but of the masochistic contract that is sealed by fusing the cruel thrill of exploiting others with the self-destructive delights of being oppressed, bossed around, hopelessly addicted, and completely dependent, creating a split subject that desires happiness but experiences only pleasure. Power now speaks less with the prohibitive ‘no’ and more with the compulsory happiness of ‘you must enjoy’ (whether you like it or not).” —Andrew Culp, A Guerrilla Guide to Refusal

In Capitalism and Desire (2016), Todd McGowan foregrounds what he says was Marx’s most profound insight: that enjoyment, rather than enrichment, drives capitalism. Capitalism is predicated on the illusion that accumulation will yield lasting satisfaction, often masking deeper forms of fulfillment. While capitalist ideology has us believe our actions are driven by a self-interested pursuit of wealth, the real motivating force is the pursuit of satisfaction, often found in the everyday sacrifices made for it, such as sacrificing our personal time, social relationships and general well-being. Capitalism is “a logic of accumulation that preys on the subject’s unconscious investment in loss.”28

Unlike Deleuze and Guattari who see capitalism as a system that appropriates and restricts desire, McGowan argues that desire itself, at least in how it is written over by capitalism, is deceptive; it obscures the pleasure derived from these sacrifices with an endless cycle of accumulation that conceals its true nature. Drawing on Freud, McGowan suggests that the pleasure principle, often understood as driving us towards satisfaction, actually serves our attachment to loss. Objects of desire are not sought for their inherent value but as representations of a lost object (Lacan’s “object a”), an object of fantasy that is nothing but an unattainable ideal or inherent sense of incompleteness in our lives. Failure to obtain the lost object leads to a gratifying re-experience of loss, continuous disappointment and the pursuit of new desires. In recognizing and embracing the satisfaction found in loss, rather than accumulation — in being content with what one already has, not only material wealth but social status derived from the conspicuous display of it — we refuse the capitalist seduction that more is always better. Through acts of withdrawal, we open up the possibility for different kinds of social organization and personal fulfillment, ones not predicated on material accumulation but on the richness of human experience and the complex nature of desire.31

“We take no pleasure in existence except when we are striving after something - in which case distance and difficulties make our goal look as if it would satisfy us (an illusion which fades when we reach it).” —Schopenhauer, On The Vanity of Existence32

Hamsa, Eye of Fatima, protect us. In her fury, our maternal deity now demands recognition. She is “stubbornly staring at us”, surprised at our “running away from (her) with our bodies, the first of (her) children to do so”.23 If we are just to return home and become more like her we will be redeemed. All the more desirable as she evades us, the Lost Earth is the lost object par excellence in our age of ecomeloncholia. She haunts and weakens us the more we look back to her as the signifier of our lost plentitude.33

Monstrous Birth

“The dark precursor is not a friend.” -Deleuze, Difference & Repetition

Romantic art often celebrates the sublime, earthly forces of nature that defy rationalization. Rather than creating order out of cosmic chaos as in classical form, the romantic hero risks channeling the overwhelming powers of the Earth. “The artist is no longer god but the hero who defies god”; they confront hell, the subterranean, inner turmoil and madness, sinking deeply into the groundless earth, that “close embrace of all forces.” While a work with many elements conventional to the Polish romantic tradition, The Lunar Trilogy is also science fiction attempting to inhabit the moon and leave the Earth behind. In encountering ancient civilizations, alien psyches and otherwordly milieus, the Silver Globe is the Old Earth of romantic literature deterrioritorializing (destabilizing or recontextualizing) onto the cosmos.21

In our post- romantic age, the Earth no longer serves as the ground of identity; it is but one limited and fragile territory among many in a vast and unknowable outerspace. Echoed by eschatological themes in Żuławski’s novels, our familiar structures of collective identity have fragmented, leaving us vulnerable to manipulation and control by the immense and invisibile forces of global corporations and government institutions; a power that only increases with the deluge of crisis. The increasingly intense and frequent natural disasters of climate breakdown are just more chaos to be managed. The artist no longer channels natural forces or speaks on behalf of a unified “people”; both the Earth and collective movements have been corrupted. The struggle now is against forces eroding both the Earth’s integrity and the potential for alternative social organization. Failure means annihilation on both fronts. The task of the artist is to counteract control, escape capture and create the conditions from which a truly new form of community can emerge, echoing Nietzsche, for “a people yet to come”, “a new earth”, one that belongs to the cosmos.21

Proceeding from modernity’s definition of humanity as homo economicus — the operative and productive subject of capitalism — what is this posthumanity to come: the romantic return to lost authenticity or the birth of something entirely inhuman and unrecognizable?

Żuławski paints a peculiar picture of a possible abject posthumanity that is half-human, half-shern. Human women who have been seduced or violated by the Shern give birth to the monstrous Mortzes, unintelligent and aggressive hybrids who despise humanity and are used as slaves and soldiers by the Shern. At one point in the film, Marek the Conqueror attempts to recruit the Mortzes to fight for him, appealing to their humanity by suggesting they must share traits with their human mothers as well as their Shern fathers. In response, they chain Marek to the earth and envelop him with their clay-like bodies, chanting enigmatically:

“Kill nothing… you - nothing. Oh Shern. Everything – pain. Sleep – pain. Day – pain. Fear. Quiet, Shern. I – Shern. When Shern sings. I – animal. You – less. You – death. I – the bow. Trees. Grass. I – see – Mortzes. You – fear. I – the run. Alone. I go. I far. You near. You fear – pain. Weight. You – voice. I – silence. We – go away, perish, drift. You – Shern. Let him sing.” —Mortzes, On The Silver Globe

The following scene cuts to a forest with Marek looking towards the sky in a rare moment of calm. “I see the earth, grass, forest,” he whispers, “I feel warm air over the path. The flight of two grey birds which I associate with death. It means… I feel fear?”

The Mortzes shame Marek, identifying his humanity with pain, fear, and death, while they themselves are silence, nature and life. The Mortzes, as part Shern, are an animal immanent to the Silver Globe that exists, as Bataille said, “like water in water”, without conscious distinction between itself and its natural environment. Marek’s consciousness, on the other hand, cut off from immanence, is an open wound. The Mortez are indeed porous, at one with the forces of nature, but they are not peaceful beasts of pasture, they are brutish and sadistic, the monstrous off-spring of war. Life is not wholly benevolent and autopoietic, animating toward the good; it is also war-like undoing and ruin. The Mortzes, brutal and monstrous, embody the dark side of becoming, challenging certain Romantic notions of noble savagery and harmonious natural order.

“Polemos is the father of all things.” —Heraclitus

Franz Rösel von Rosenhof - ‘The Earth after the Fall of Man’ (1690)

Franz Rösel von Rosenhof - ‘The Earth after the Fall of Man’ (1690)

Deleuze’s differential ontology can help us tease out how Żuławski’s work, as an assemblage, both repeats Romantic refrains while gesturing toward a posthumanity beyond redemption. In the romantic return to an idea of nature as a lost and once perfect harmony between us and the world, we repeat what Deleuze called philosophy’s dogmatic image of thought — an implicit, uninterrogated model of what it means to think. Claiming to begin free of all presupposition, philosophy’s image of thought assumes a natural coherence between all thinkers, cogitatio natura universalis, and conceives the activity of thought as an abstract and disembodied faculty of pure reason, somehow transcending particularities of situation and perspective, taking as given a harmonious congruence between our thought and the world. The philia in philosophia is the assumption the other is our friend or lover and not indifferent to our very human idea of the good.

While Deleuze is most often celebrated as a philosopher of positive affirmation —vitalism, productivity, creativity— there is a dark side to the Heraclitus-inspired flux of differential ontology that is often overlooked, if not suppressed (that said, the opposite is also true when poststructuralism is caricatured as solely deconstructive or obstructive). Far from the progress of reason, the history of philosophy has been the development of an error: the privileging of identity over difference. Deleuze’s aim is to think difference in a way that does not reduce it to mere opposition or deviations from fixed identities. Thought fails when it reduces encounters with the unfamiliar to already established categories or concepts (recognition through representation).15

The task of philosophy is to open up new possibilities for thinking. While Deleuze’s readings of past philosophers are notoriously “Deleuzian”, he philosophized with the intention not to replicate thought through repetitive exposition, but to free thinking from dogma and create new concepts. He once described writing about other thinkers as an act that is as equally a betrayal as it is loyalty, likening it to “taking an author from behind” and giving them “a child that would be his own offspring, yet monstrous.”25

“A book of philosophy should be … a kind of science fiction … How else can one write but of those things which one doesn’t know, or knows badly? It is precisely there that we imagine having something to say. We write only at the frontiers of our knowledge, at the border which separates our knowledge from our ignorance and transforms the one into the other.” —Deleuze, Difference & Repetition

In Deleuze’s metaphysics, existence is a chaosmos not inherently geared towards meaning. Existence is thought in that it solves problems, becoming something new with each moment, without origin or telos. It is the eternal return of difference, not the motionless, unchanging repetition of the same. All identity is derivative of difference. As the non-representational dissonance and contingency of differential relations that generates existence and thought, difference in-itself is defined by what it is not, rather than what it is. We can think of it as a placeholder (object = x) recognizable only through its effects, because it has no identity other than that which it lacks. It is “invisible and imperceptible” in that it differs from itself with every repetition, becoming apparent through non-linear events as they unfold. Thought is other to itself; it emerges from an “unrecognized and unrecognizable terra incognita” that exceeds it.12

Confrontation with the unknown is never safe or friendly. Transformation is often violent in its unassimilable disruption of the familiar. As Hannah Stark has said, “the space in which difference manifests itself is one of discord, monstrosity and violence.”34 Creation and destruction are not a binary opposition but correlative processes of the same vector of transformation. It is not conservation, stability or harmonious interaction that holds systems together (conatus), but the potential for disruption and transformation introduced by their most creative and destabilized elements, their excess or surplus value, like an arrow, pushing assemblages into uncharted territory (will to power). Ethics involves confronting the unknown and the negativity of difference, allowing for difference in-itself, regardless of its potential challenge to accepted meaning, agreement or common sense.

Canadian Wildfire. Credit: Alamy

Canadian Wildfire. Credit: Alamy

In his critical re-evaluation of Deleuze and Guattari’s philosophy, Andrew Culp gives monstrous birth to Dark Deleuze (2013). Focusing more on their political and strategic thought than their metaphysics, Culp challenges the prevalent “canon of joy” that celebrates Deleuze and Guattari as primarily thinkers of affirmation, a reading that reinstates a positivity and productivity readily assimilatable by neoliberal capitalism. Culp is critical of a world captured by compulsory happiness, decentralized control, overcommunication and visibility. Indicative in the expert precision and brevity of his writing style, Culp points out it is the operation of n-1, negativity and subtraction, rather than positivity and addition, that is the revolutionary legacy in Deleuze and Guattari’s work. Rather than morally prescriptive or metaphysically ponderous, as war machine, their thought is a tactical and strategic methodology of locating what holds a system together and pushing it into crisis by subtracting a dimension, making the desert grow. Rather than a philosophy of proliferating concepts just for the novelty of it, “Dark Deleuze” is about keeping “the dream of revolution alive in counterrevolutionary times” by fostering a necessary “hatred of this world” and disrupting the addictive joy that has captured us.

As Culp points out, capitalism’s success over its alternatives is because it is more exciting. Any alternative may need to be even more exciting, beautiful, young and enchanting in order to win us over; and what is possibly more exciting than capitalism than its destruction? Capitalism isn’t an accident we can just step outside of and back into a world of organic wholeness. It has to be undone. “Dark Deleuze creates concepts only to write apocalyptic science fiction.” Culp is explicit that he is not calling for the violent destruction of your neighbour’s private property. The “Death of the World” targets objects of thought (such as connectivity and positivity) that repeat in their failed claims to save the world. It critiques their proponents and subtracts them as relevant. Transformation not genesis, un-becoming not assemblages, escape not acceleration, interruption not production. “I mean the abolition of private property, work, and all of the intolerable forms of oppression it enables (patriarchy, racism, ableism).” We are to give up on all the reasons for saving the world as it is, with one caveat, “never believe that darkness will be enough to save us”.27

“So while there is no man, nature also must vanish.” —Culp, Dark Deleuze

Similarly, in the essay Nature’s Queer Negativity (2019), Swarbrick emphasizes Deleuze’s darker side of difference; the gravity of negativity, unintelligibility, and intolerability in differential ontology. Focusing on the work of Karen Barad, namely Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning (2007), Swarbrick critiques the neovitalist turn in queer and ecological theory, contrasting Barad’s redemptive ethics of repair with Deleuze’s “asignifying ontology of self-dismissal”. For Barad, matter is meaning-making; ethics and matter are one and the same; all being, knowing, and appearing are “intra-actively” entangled, yielding an ethics of “response-ability” and care amongst all human and nonhuman others. Nature is our very human and rational idea of “the good”. Barad’s agential realism fractalizes correlationism, which only radicalizes the Kantian conditions of meaning that once belonged exclusively to subjectivity and disseminates it throughout the universe.30 This attempt to overcome loss through meaningful connection, symbiosis and consilience in matter itself, treats loss as if it were merely contingent, not constitutive, of desire.28

Swarbrick plays off Deleuze’s use of the word intagliated (a term Deleuze didn’t use often but has interesting resonance). In intaglio engraving, an image is incised into a metal plate with a sharp tool or acid which “bites” away the surface. The areas cut or carved away hold the ink that produces the image printed. The image underscores how the act of creation always involves an element of aggression or violence, a forceful disruption. Repair and aggression are intagliated.30 Swarbrick calls for a queer naturalism that understands nature as pharmakological, both “cure and harm in the same movement.” In pastorializing nature, reparative ethics sanitizes critical aspects of violence and aggression integral to understanding and engaging with ecological relations and politics. Life is non-ameliorative; it is fundamentally explosive, as destructive as it is creative, as irreducibly incoherent as it is coherent. Matter is “structured by loss”.30

Intaglio by Frederik Ruysch, ‘Thesaurus anatomicus; skeleton monument’ (1701–1716)

Intaglio by Frederik Ruysch, ‘Thesaurus anatomicus; skeleton monument’ (1701–1716)

In his more recent work, The Environmental Unconscious (2023) and short essay Destituent Ecology (2023), Swarbrick shifts focus from Deleuze’s differential ontology and affirms fidelity to the split subject of the psychoanalytic tradition of Freud and Lacan, understood as fundamentally constituted by nonrelation. Subjectivity is constituted as loss, shaping relations retroactively through its absence. The ecological subject cannot escape the obscene jouissance, the paradoxical pleasure, that defines it as a breach or tear. This is the uncountable remainder that ecological entanglement fails to think. He revises Barad’s “relations precede the relata” to “nonrelations precede the relata,”33 foregrounding thinkers and poets that articulate life and ecology as loss and disarticulation. This is not to say nature doesn’t think or have languages, it does, but it is “language without the human”. As Swarbrick says beautifully, “life sings endlessly of its own incompletion and failure of full speech.”28 In spinning everything into a web of recognizable human-like relations we recreate nature in our own image, and “deny the inarticulable its voice, its power to make nature stutter”.28 We share in the same existence as loss. In aligning matter with poetic form as loss, these poets show us how to “enjoy loss and resist the promise of future gain”.28