Iceland: Alþingi

“Without love, there are no ties or alliances.” —Michel Serres, The Natural Contract

Established in 930 CE amidst the northernmost fissures of the Mid-Atlantic ridge, the Alþingi (National Parliament of Iceland) is the world’s oldest surviving parliamentary institution. Formed by Norwegian settlers with an aversion to centralized authority, it was an annual outdoor assembly where chieftains could decide on legislation and administer justice. Free citizens from across Iceland would come to trade, share stories, form alliances and settle disputes. From the height of a rocky outcrop called the Lögberg (Law Rock), the elected Lögsögumaður (Law Speaker) would recite the laws of the land to those assembled in the natural amphitheatre below. All attendees were given opportunity to voice concerns on relevant matters from the Lögberg.

þing (thing) in Old Norse is derived from þingą, meaning assembly or meeting. In Old Germanic, “Ding” was an issue negotiated before a tribunal. Long before signifying an object without using its specific name, “thing” meant an issue that brought people together precisely because they disagreed. Heidegger, with idiosyncratic etymological rigour, spoke of “Das Ding” as a gathering “especially for considering things in conversation, a controversial gathering”(Heidegger) where heaven and earth, the divine and human beings come into relation with one another.

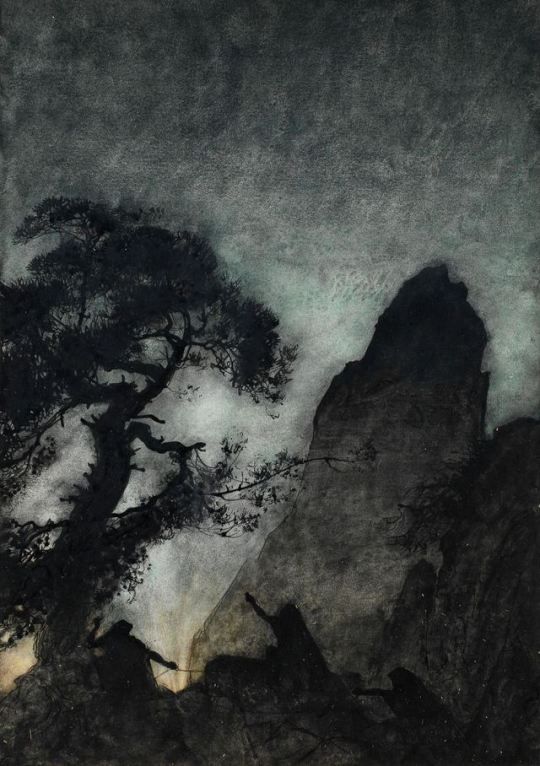

The exact location of the Lögberg is unknown today, but from anywhere along the heights of Þingvellir (assembly fields), one can look out across what feels like the entire world. Fog-laden grasslands of Skógarhóll stretch to the horizon, crisscrossed by the shimmering Öxará river as it winds into Þingvallavatn. Gathered in the open air, all local denizens are present at the Alþingi — Dwarf birch and wildflower, Rock ptarmigan, Brown trout, Arctic fox, boulders of basalt dressed in century old lichen swarmed by day young gnats — each an active participant in a larger network of bonds, negotiating on its own terms. While storm clouds shift erratically above, below tectonic plates drift slowly apart across millennia. In audience with the sun and sky, all are at mercy of open systems that exceed our ability to manage them and challenge our everyday comprehension of time.

Natural Contract

“The Earth speaks to us in terms of forces, bonds, and interactions, and that’s enough to make a contract.” —Michel Serres, The Natural Contract

In The Natural Contract (1990), Michel Serres evokes a team of mountaineers as metaphor for the social contract. Tied together by responsibility for each other’s survival, they are also necessarily anchored to the cliff face. The mountain might not speak a human language but has ways of making itself heard. It must be negotiated with. Each piton is a pact. “The group finds itself bound and submitted not only to itself but to the objective world … a natural contract joins the social contract.” One can imagine the Lögberg at Þingvellir as an anchor to which all social accords were once tied to the landscape. A bond that, Serres observes, has been severed.

For Serres, everything is communication, information exchange, signal and noise. The natural world isn’t a mere collection of objects, but complex networks of relations between the living and non-living. To think along an artificial divide between our social world and the natural one that sustains it is gravely misguided. Yet, in vain, we try to abstract our social contracts from the natural cord that weaves through everything and binds them.

“Through exclusively social contracts, we have abandoned the bond that connects us to the world, the one that binds the time passing and flowing to the weather outside … the bond that allows our language to communicate with mute, passive, obscure things, things that, because of our excesses, are recovering voice, presence, activity, light. We can no longer neglect this bond.” —Michel Serres, The Natural Contract

Today, we live a-cosmically, cut off from the world of things. We’ve tried to master and possess them, systematically writing them out of our politics and institutions, neglecting their demands while living off them parasitically. And now, they push back. Humanity has become geological, as massive as the tectonic plates at Þingvellir. Our actions impact all networks on a global scale. Serres calls for a natural contract, one of symbiosis and reciprocity that recognizes each collectivity shares the same world. Without this new alliance, we sever our lifeline and fall from the precipice.

Different Planets

“My dear fellow, you seem to live on another planet.” —Bruno Latour, Fictional Planetarium

Closely following Michel Serres, Bruno Latour, in We Have Never Been Modern (1991), would propose the idea of a Parliament of Things — a political assembly of provisional collectives of humans and nonhumans. According to Actor-Network Theory, “things” participate in shaping social relations as much as humans do. “Society is not made up just of men, for everywhere microbes intervene and act”. This would not be an attempt for certain groups, such as scientists, to assume an authoritative voice for things, but explore practical ways to include nonhumans in a shared politics, to assemble and have matters of concern addressed equally as a collective. A Constitution, building from Serres’ natural contract, would give legal framework for contesting, for example, issues of climate crisis.

“We scarcely have much choice. If we do not change the common dwelling, we shall not absorb in it the other cultures that we can no longer dominate, and we shall be forever incapable of accommodating in it the environment that we can no longer control. Neither Nature nor the Others will become modern. It is up to us to change our ways of changing.” —Bruno Latour, Fictional Planetarium

Latour would later reflect on how he, and Serres, had been too optimistic. Imagining that a social democracy could be extended to all things was based on the naive assumption of a common world, where the possibility of agreeing to disagree was even possible. For Latour, we’ve moved well past a time of possible action to one of war and tragic dissent. How can we talk about the expansion of an inclusive parliament when the parliamentary model itself is contested, evident with anti-democratic voices that now only rise in volume the more the planet breaks down?

“We live on different planets,” Latour said, characterizing our fundamentally irreconcilable world views as a fictional planetarium. From Planet Globalization’s death-wish of unlimited growth, to the wet dreams of Mars colonization by megarich on Planet Exit, to the neo-nationalist’s reactionary blut und boden fantasies on Planet Security — today we have drifted apart. We are as foundationally divided among ourselves as the continental plates at Thingvellir.

“Right now, the probability that [ planets ] will coalesce to make one common world is nil — and I would say, fortunately so, since the largest of all, [ Planet Security ], is probably the darkest and holds the least promise of unifying the political situation. Activists and politicians may now understand that one qualification should be added to the project of designing for the planet — the question, For which planet?” —Bruno Latour, Fictional Planetarium

More-Than-Human

“How shall earth be referred to? By calling it Ymir’s flesh and mother of Thor, daughter of Onar, bride of Odin, rival of Frigg and Rind and Gunnlod, mother in law of Sif, floor and base of winds hall, sea of the animals, daughter of Night, sister of Aud and Day.” —The Prose Edda

In Old Norse verse, kennings are poetic circum- locutions that refer to things of significance without naming them directly. They describe a subject in relation to landscapes, characters or events from other stories, weaving an intricate tapestry of references through a play of differences. As cultural shorthand, familiarity with kennings binds collective memory and social cohesion, an art mastered by the #skalds and orators of the Alþingi who knit community through words.

Kennings shape a way of thinking that recalls we are nothing but our relations. We do not first exist then choose to enter into contracts with things; our very existence is composed of and defined in participation with them. Things do not lie in wait for us to name them, to be invited or allowed into our social circles. They are their own authority and make their own laws. In utter dependence, we belong to them. Late if life, Latour would say the question now is no longer how do we grant rights to things, but how can we request the rights for our existence from them.

In this light, the more-than-human serves a social function traditionally akin to the divine — a greater authority we must humbly bow before and ask permission of, no matter how impersonal or unruly as gods they may be. Latour named Gaia, after the goddess in Hesiod’s Theogony. Michel Serres wrote of forgotten strange acts, a practice that “spins, knots, assembles, gathers, binds, connects, lifts up, reads, or sings the elements of time.” (Serres) Not religion as a claim to objective truth, but as lived performance, embedded in our world but in participation with the greater cosmos, lost rituals that provisionally bind individuals to collectives, to the weather outside, in communication with things, face to face with those from which we take, recalling our responsibility to live symbiotically.

“To live in a boundless landscape and a close-knit culture in which everything matters and everything is connected is a kind of magic … Like generations of Inuit, I bonded with the ice and snow.” — Sheila Watt-Cloutier

Serres passed away in 2019 and Latour in 2022. We can thank them for their contributions to continental philosophy while recognizing that much of what they came to articulate in their particular vernacular — rooted in ancient Greece and European history — has been evident for many lived Indigenous traditions all along. Isabelle Stengers is more explicit about problematizing her situatedness as a writer and philosopher of science, calling herself “daughter to a practice responsible for many divisions.” (Stengers)

Modern thought is heir to operations of cultural and social eradication in the name of progress and reason. Stengers suggests animistic magic as a means to break the spell of hegemonic rationality and exploitative capitalism that continues to reduce and divide, dismember and demystify. Pagans and galdramaður of Iceland were radically pragmatic in spinning affects and transversal connections across many worlds. They knew the more-than-human demands care and reverence. We might look back and “sneer”, to use Stengers’ words, at both those damned for magic and those who damned them as superstitious, but the situation now demands we choose sides.

Drowning Pools

“The smoke of the burned witches still hangs in our nostrils.” — Starhawk

The Alþingi was a site of social gathering and also a court that administered punishment. In the 17th c, women found guilty of crimes such as adultery and infanticide were tied in sacks and drowned at Drekkingarhylur (Drowning Pools). There were numerous confirmed burnings related to sorcery.[^]

What is needed today is not a return to a superstitious past, but a reclaiming of those spells we can learn to reworld in the coming ruins. What fate the Norns have in store for us may be answered by what stories we weave that gather and assemble the tattered threads of what has been divided.

Mightily wove they the web of fate,

While Bralund’s towns were trembling all;

And there the golden threads they wove,

And in the moon’s hall fast they made them.”

— The Poetic Edda, Helgakviða Hundingsbana

“The Three Norns” (1911) by Arthur Rackham

“The Three Norns” (1911) by Arthur Rackham

Works Cited

Bellows, Henry Adams. “Poetic Edda: Helgakviða Hundingsbana”. 1936.

Latour, Bruno. “A Fictional Planetarium”. 2019. →

Serres, Michel. “The Natural Contract”. University of Michigan Press, 1995.

Stengers, Isabelle. “Reclaiming Animism”. E-flux, July 2012. →

Sturluson. Snorri “Edda”, trans. Anthony Faulkes, 1987.