Ciaran Carson

“Halfway through the story of my life I came to in a gloomy wood, because I’d wandered off the path…” — The Inferno of Dante Aligheri (trans Carson)

I first encountered Irish poet Ciaran Carson as a translator of Dante’s Inferno. Love my Longfellow & Doré edition, but while beautiful, it is a slow and challenging read. Carson’s verse is accessible while preserving the poetic quality of the original. Recalling that Dante “took the greatest delight in music and song; and with all the best singers and musicians of those times he was in friendship” (Boccaccio), Carson modeled his translation from Medieval Italian on the expressive energy of the Irish-English ballad; a form that shifts effortlessly from vulgar to mellifluous as it “moves from place to place”, whether it be through the streets of Belfast or the depths of Inferno.

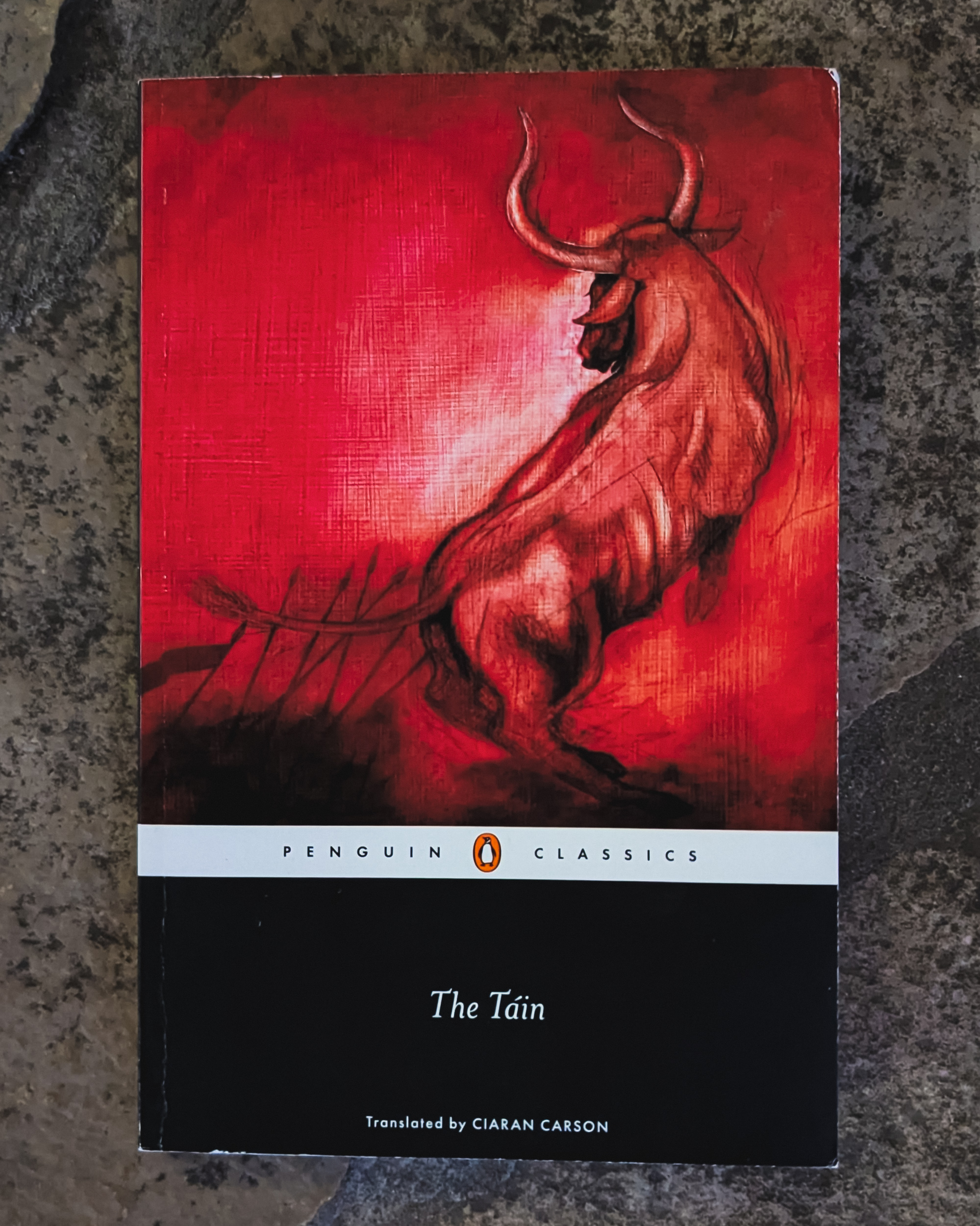

Carson’s Inferno lead me to his translation of Ireland’s epic Táin Bó Cúailnge. In the spirit of “dindsenchas” (lore of high places), the Táin is largely a topographic account of place names and their alleged etymologies, including associated characters and events, revised by many voices over many generations. Carson describes it as less of a linear storyline and more like wandering through a landscape, or “like a series of songs with variant airs”. Much of the action in the Táin takes place at fords —druidic spaces, portals to the otherworld— where waking reality and the twilight of imagination, memory and prophecy meet.

Medb: ‘For our army, Fedelm, what lies ahead?’ Fedelm: ‘I see it crimson, I see it red.’ — The Tain (trans Carson)

Bardic poets chart place, story, and song into mnemonic maps, continually renewing and preserving cultural memory through its performance. Fitting, then, that Carson was also an accomplished musician. Dissatisfied with stuffy lyric poetry at the time, he immersed himself in traditional music. “With the music – you’re right up against the stuff, it’s hitting you from all sides, it’s alive… It’s not about withdrawing into your cell to compose these careful utterances about life.” With ‘The Pocket Guide to Irish Music’ (1986) and ‘Last Night’s Fun’ (1998), Carson’s prose took on the immediacy, spontaneity, and festive sociality of the Irish session.

As concerned with breakfast, whiskey and cigarettes as it is traditional music, ‘Last Night’s Fun’ is really about language, memory and time, evoking the same mythic liminality found in Carson’s translations of Inferno and The Táin.

The prose rolls in Beat mode through the rambling histories of Irish tunes and the English folk and American Old-time that influenced how Carson’s generation interpreted and played them. Recalling legendary performances, he describes tune-playing like a cosmic machine with spectral parts that revolve and interlock to arrange the fractal patterns we experience as time.

The machinery is imperfect, its aim indeterminate, like some “strange poteen- induced passage in which time and space and custom have undergone some tremors of dimension, and come out slightly wrong.” While each tune is a well-worn path, it’s the wanderings off that path —the difference with each repetition— that express its creative force. Forever negotiated in the here and now, a tune has no ideal form. The old gods play by ear, not divine notation.

“We are fragile, and it is the morning after; rather, it is early afternoon, and we have settled in a dusty sunlit corner of the empty pub … sunshine filters through an etched-glass window and lights on fiddle-cases, pints and flute-boxes … Our talk is desultory till we think to play a tune, and we are all reluctant. Yet we start because we have to … We sense each other’s playing in the way the Zodiac arrives at planetary conjunctions, and we can do no more than play the pattern out. And though the stars, by now, are out of line with what they were two hundred years ago, we have been moved to know that until now we had not played this tune. We did not know its beauty, nor had we realised the marks of other hands that knew it, and had passed it on to some they hoped would eventually manage to figure out its gorgeous shape. We repeat this same tune many times [until] we know it’s time to stop, since we have gained a century in those few minutes of horology. Then we were like some watchers of the skies … we were silent as we contemplated time in all its mirrored constellations.”